“[…] AND THE EARTH OF HER OWN WILL, ALL THINGS MORE FREELY, NO MAN BIDDING, BORE. “

THE GEORGICS, VIRGIL

Orthós is one of ten sections of Lanfranco Aceti’s installation titled Preferring Sinking to Surrender which was conceived by the artist for the Italian Pavilion, Resilient Communities, curated by Alessandro Melis for the Venice Architecture Biennale, 2021. The ten sections are: Tools for Catching Clouds; Preferring Sinking to Surrender, Part I; Preferring Sinking to Surrender, Part II; Sacred Waters; Le Schiavone; Orthós; Seven Veils; Signs; Rehearsal; and The Ending of the End. These sections, singularly and collectively, create a complex narrative that responds to this year’s theme How Will We Live Together? set by Hashim Sarkis, curator of the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale.

The works of art — realized as a series of performances, installations, sculptures, video, and painting contributions — are part of the installation at the Italian Pavilion from May 21, 2021, to November 21, 2021, the opening and closing dates of the Venice Architecture Biennale.

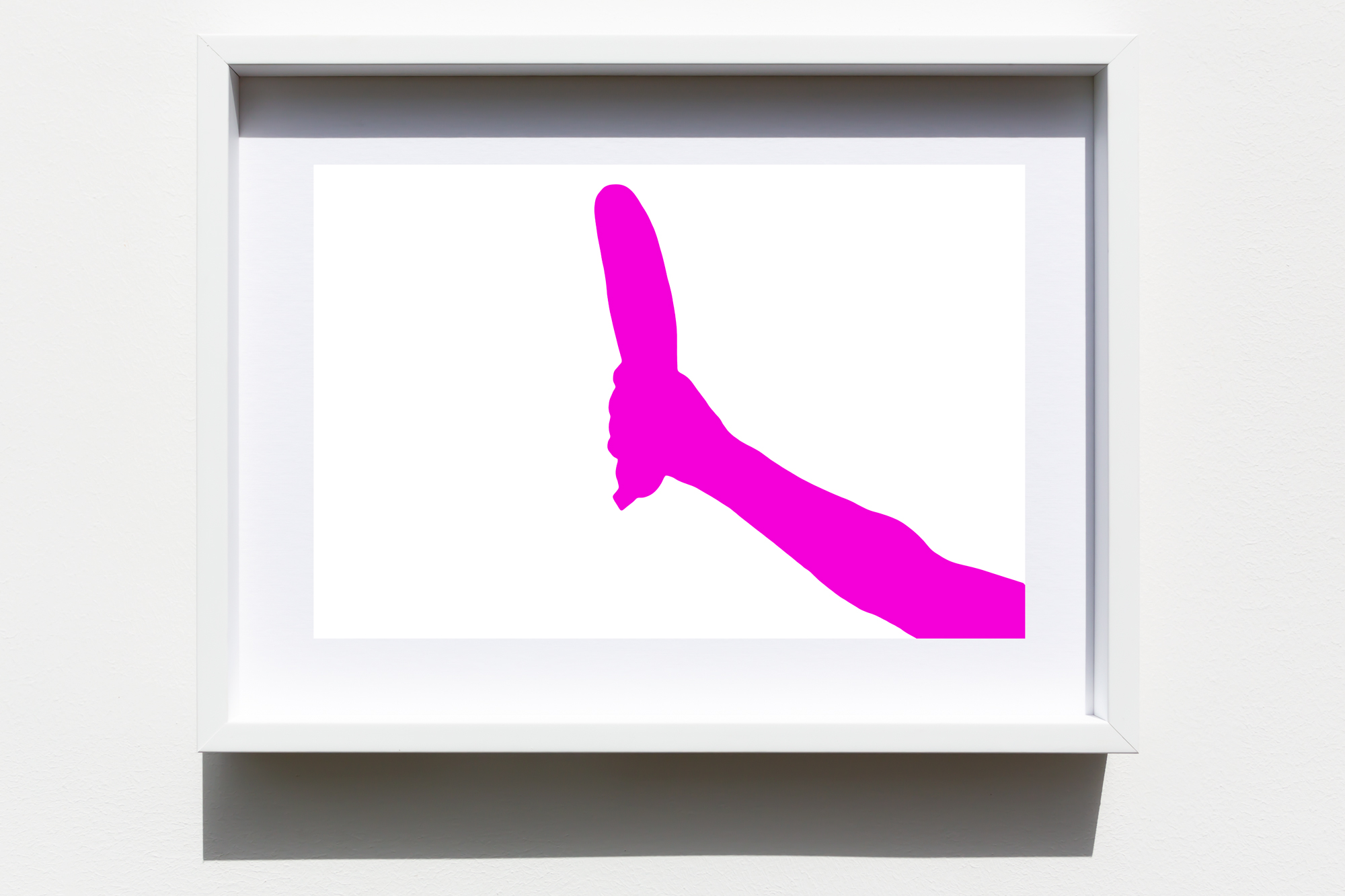

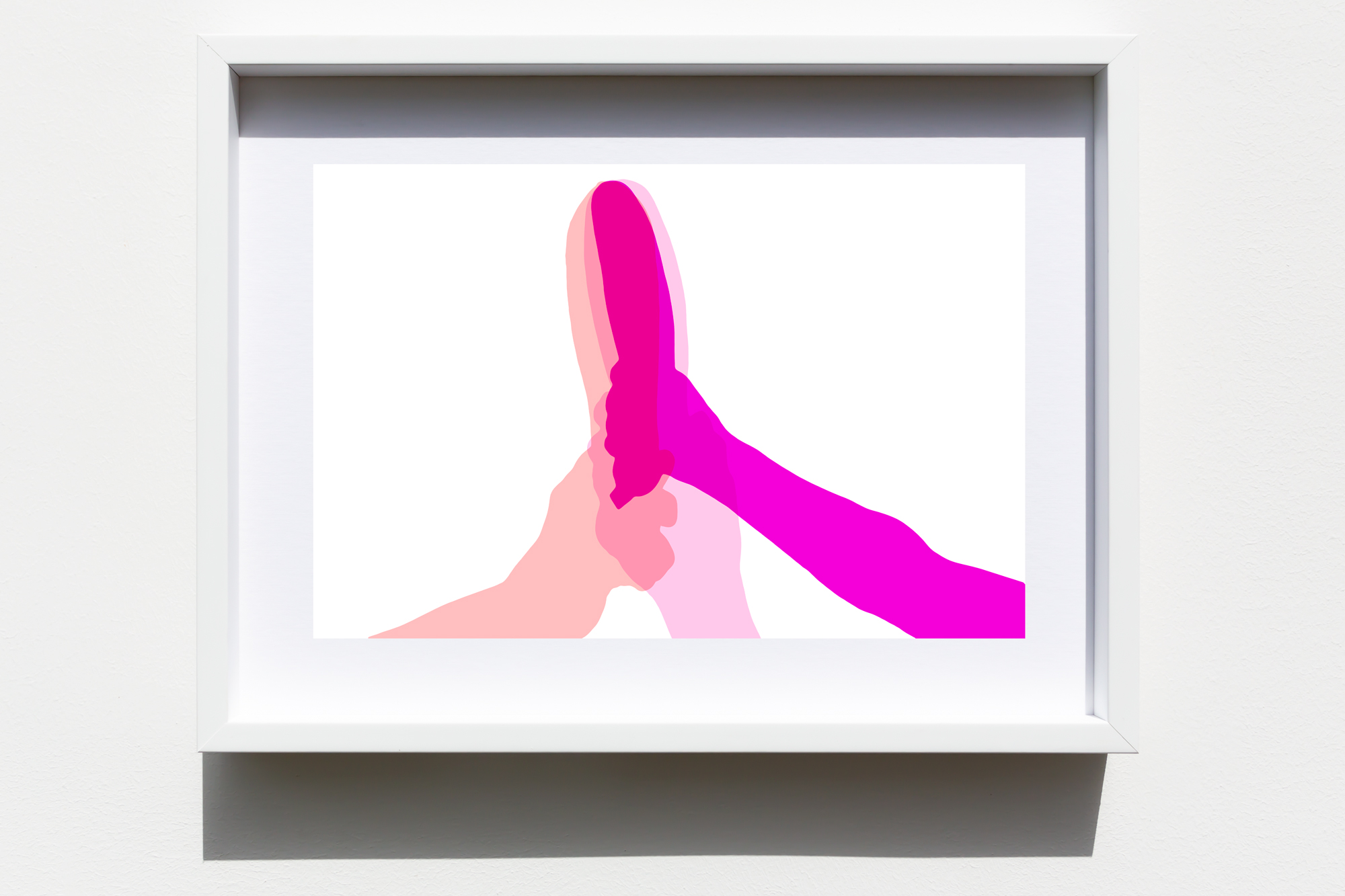

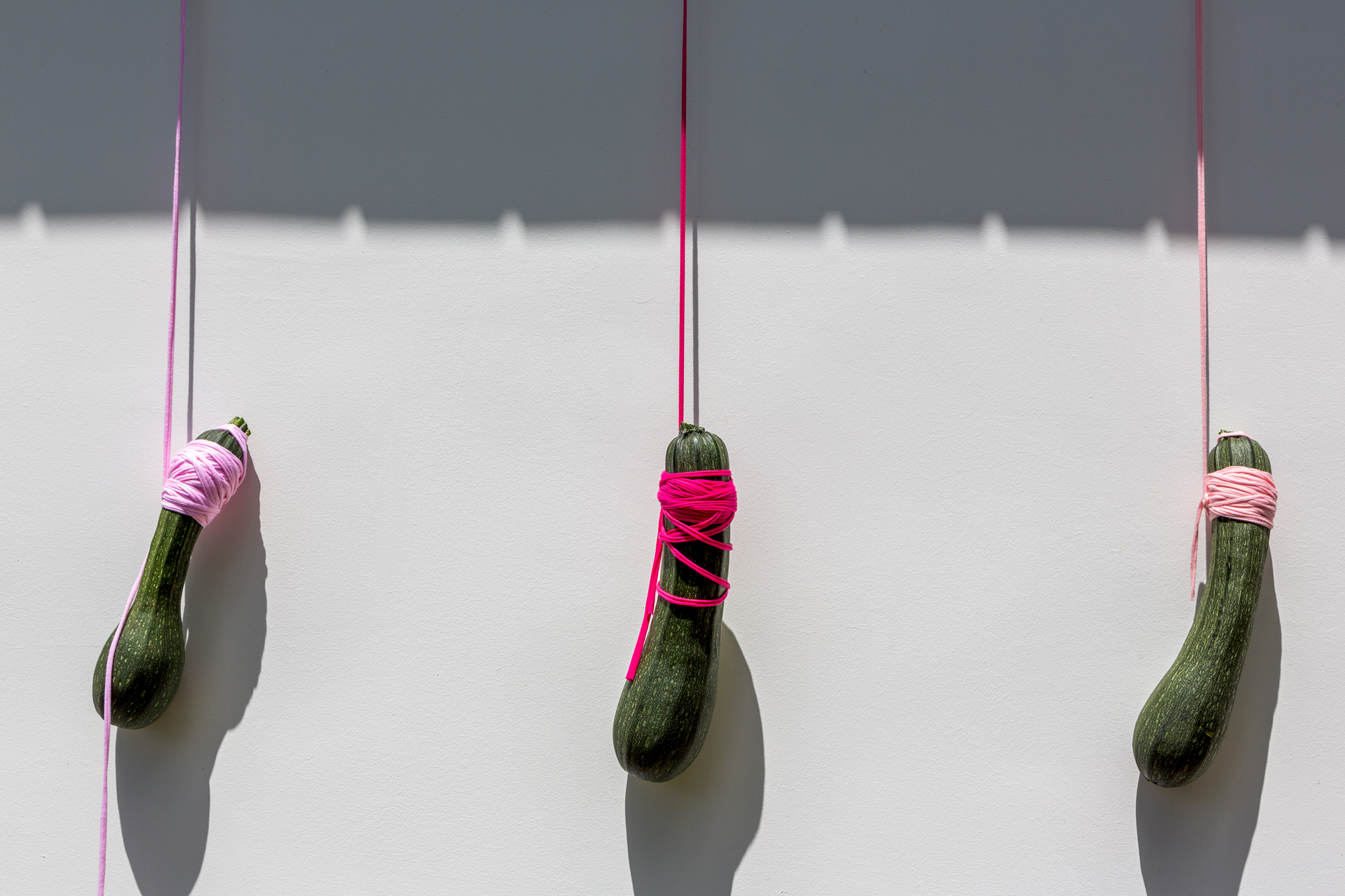

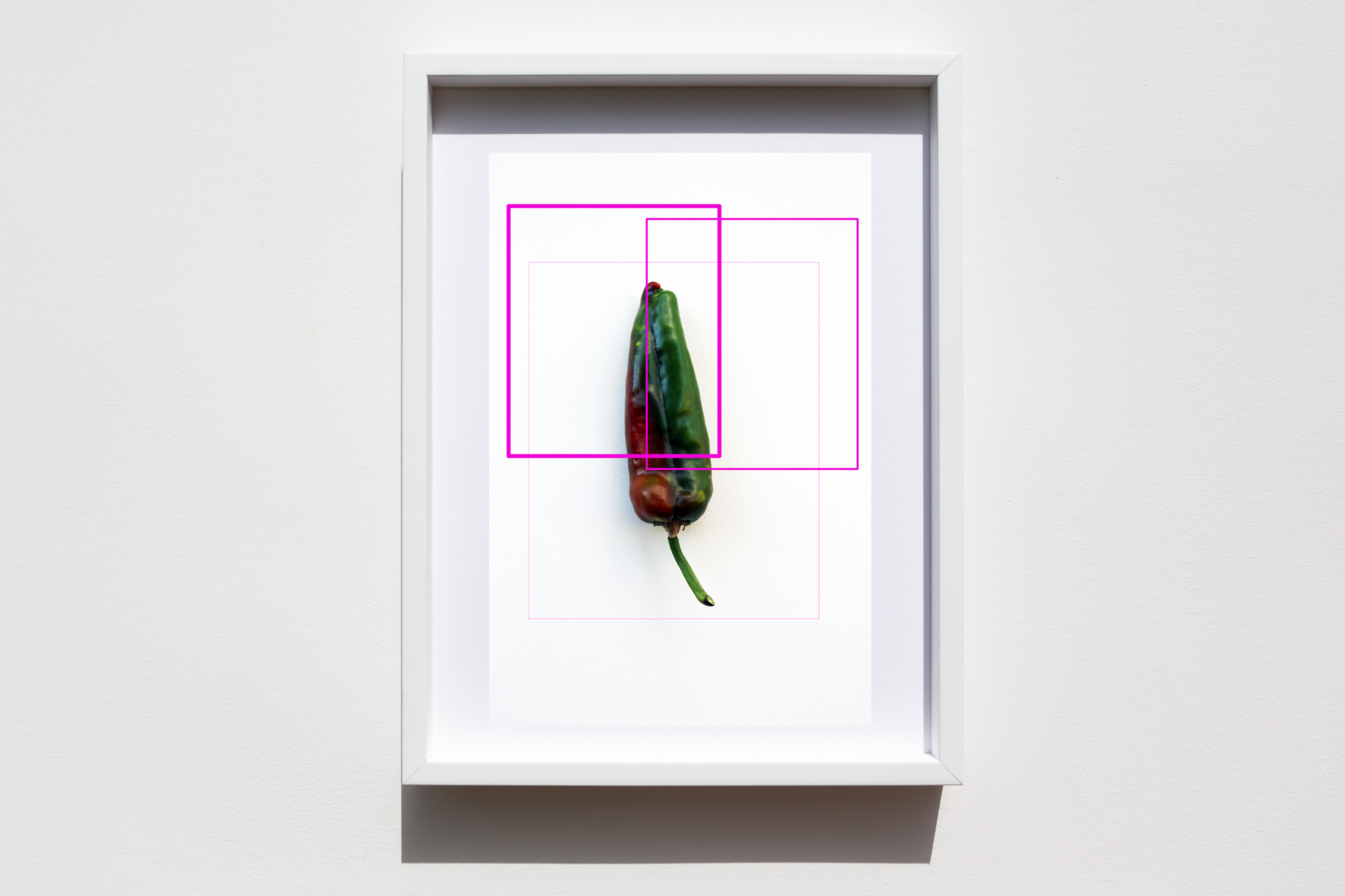

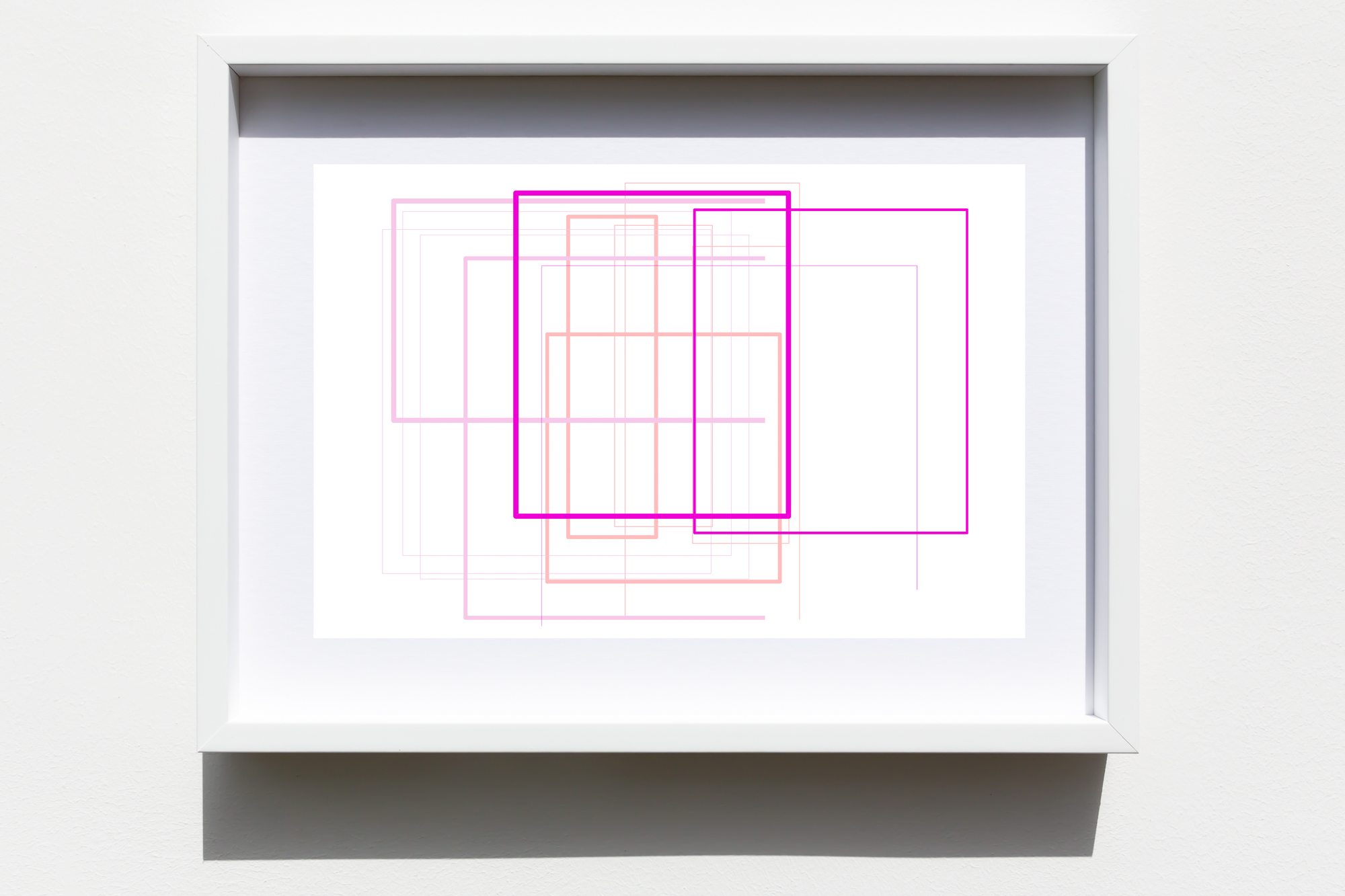

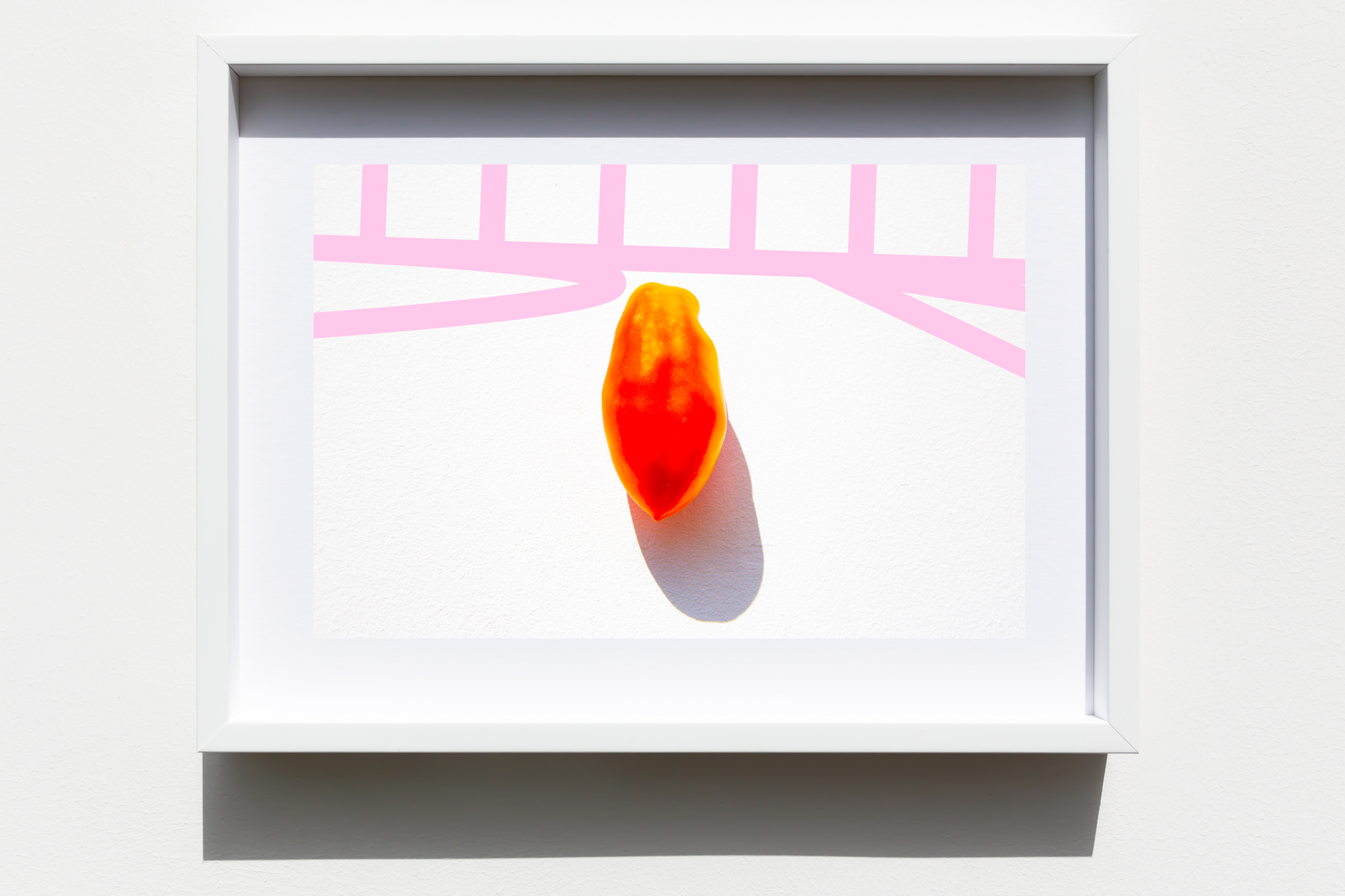

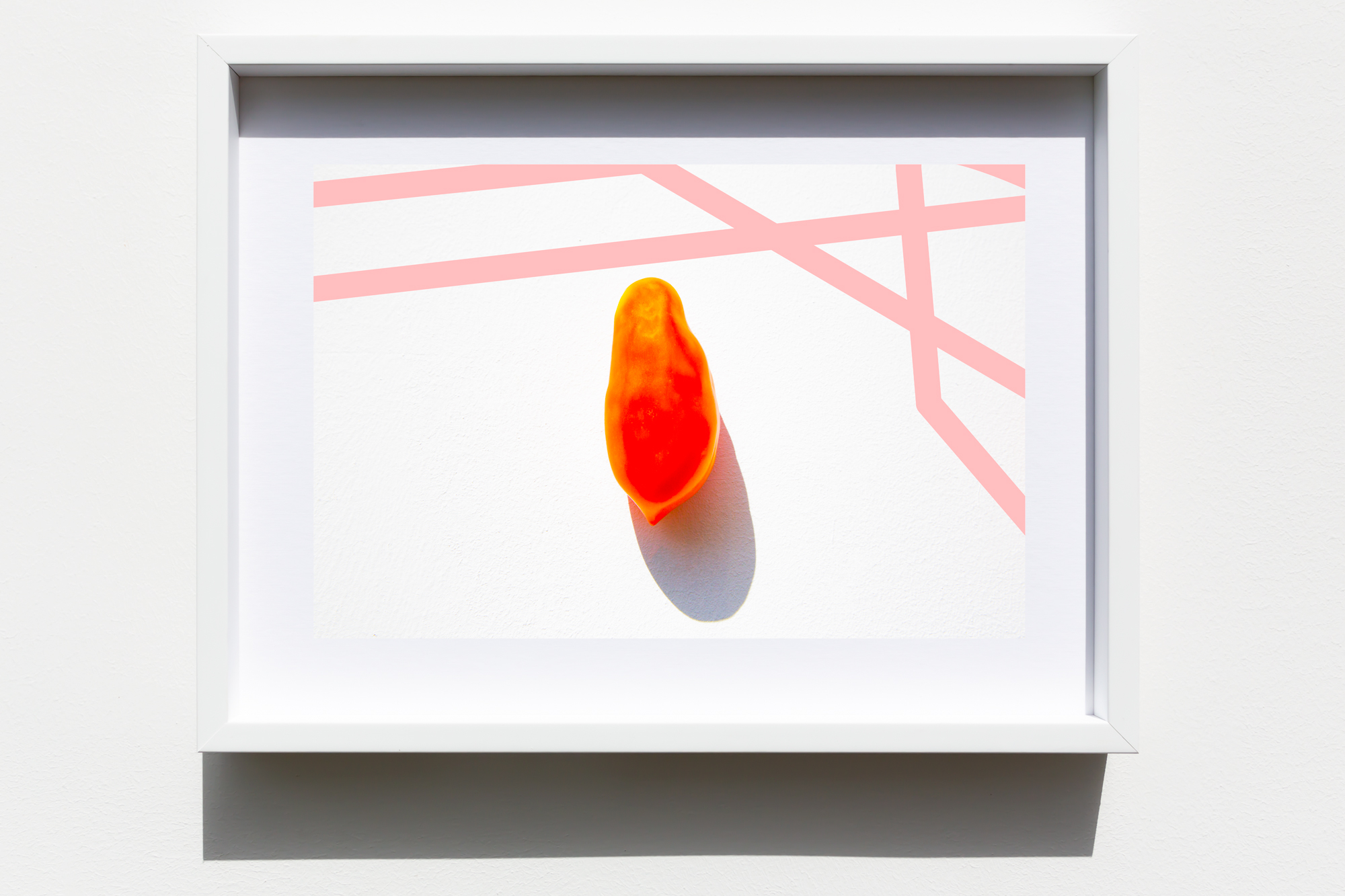

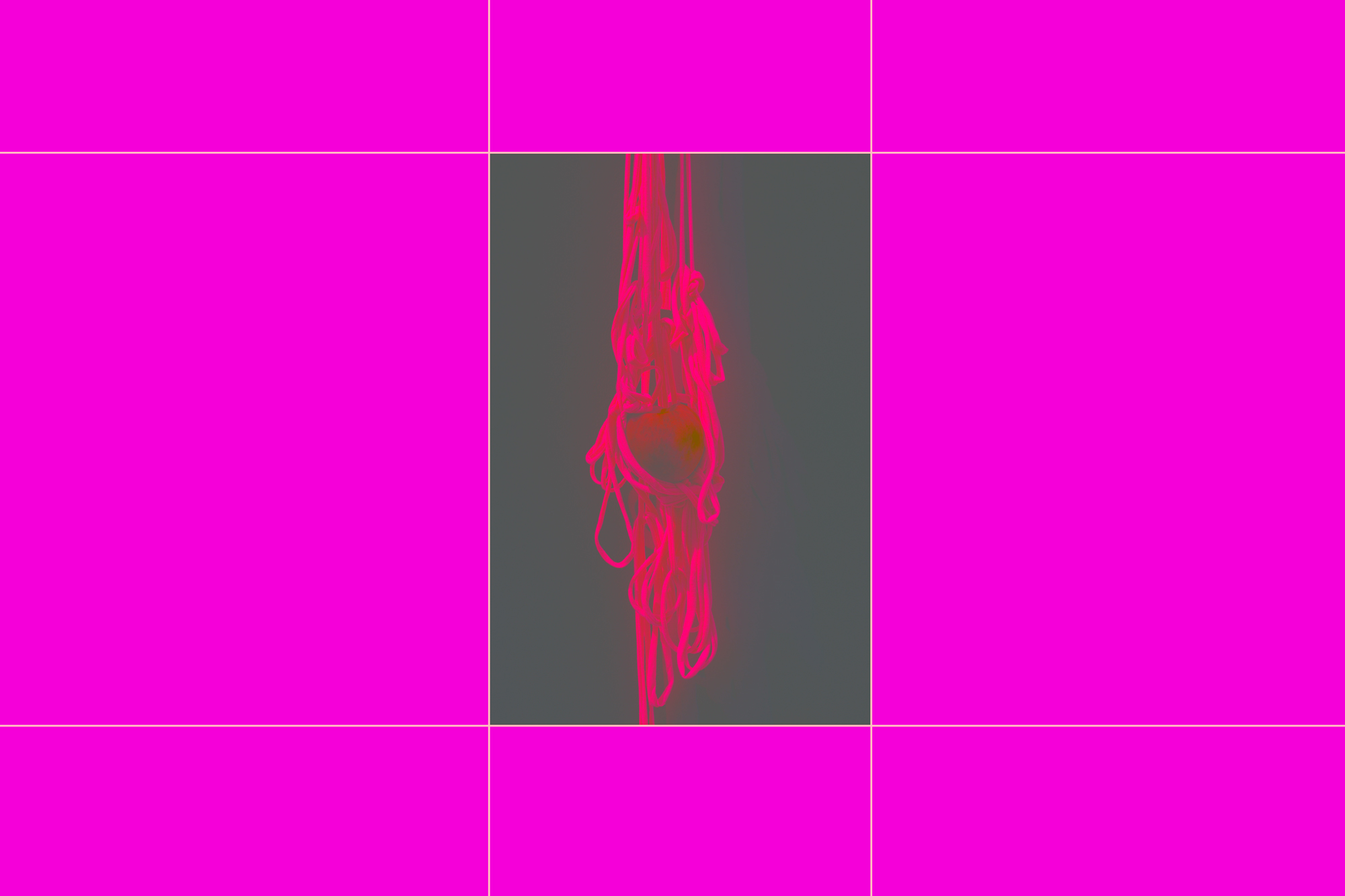

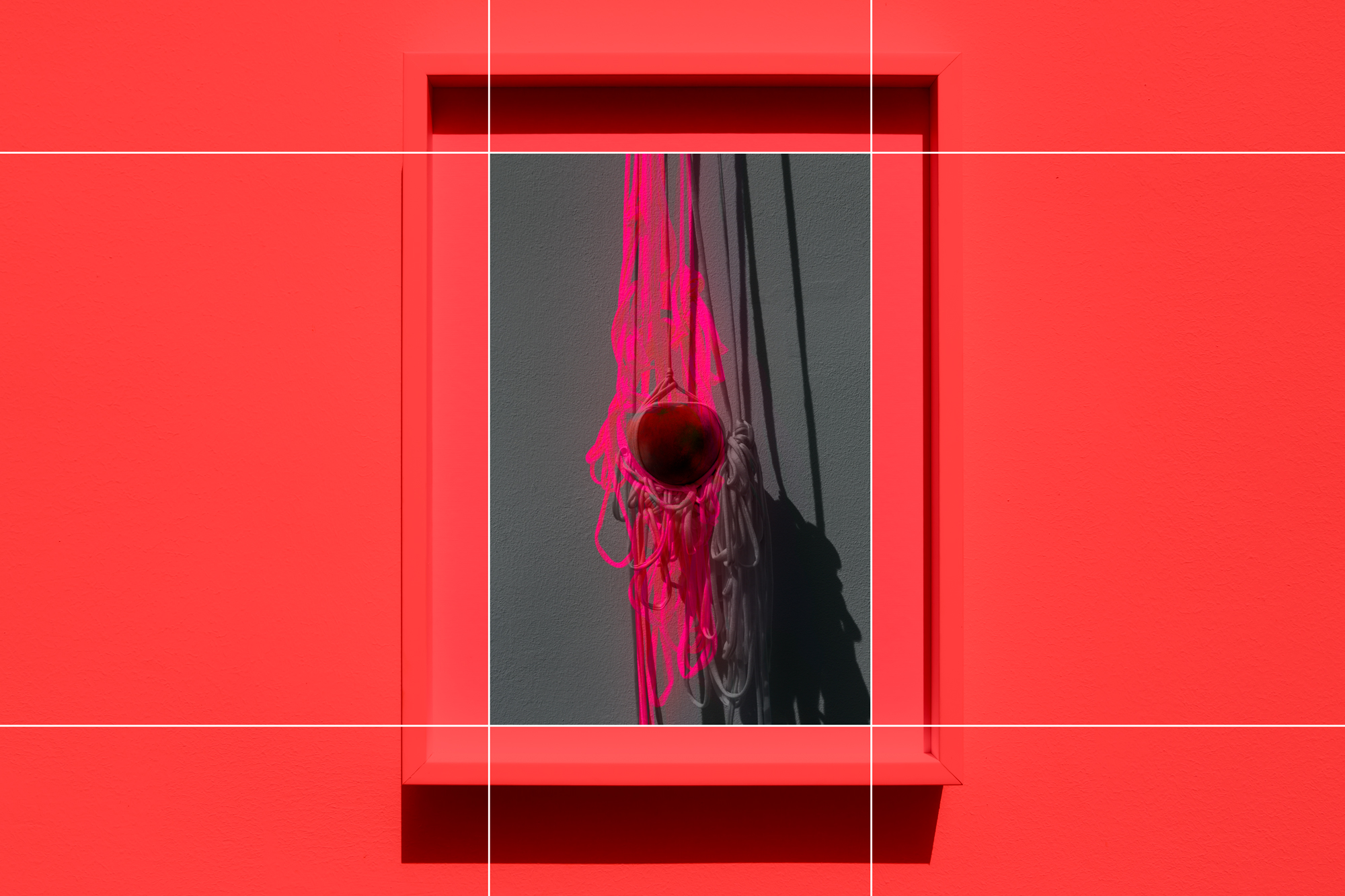

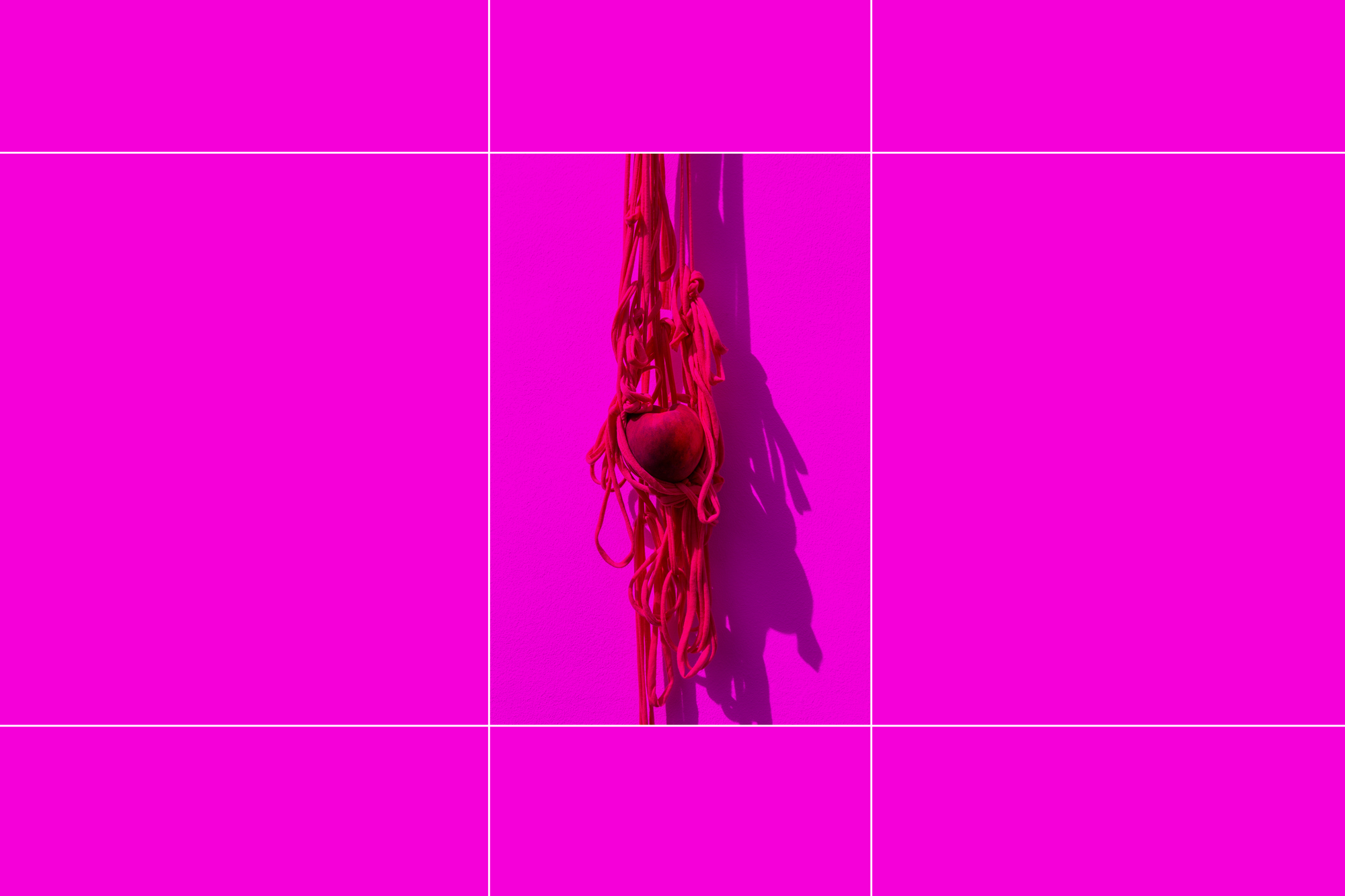

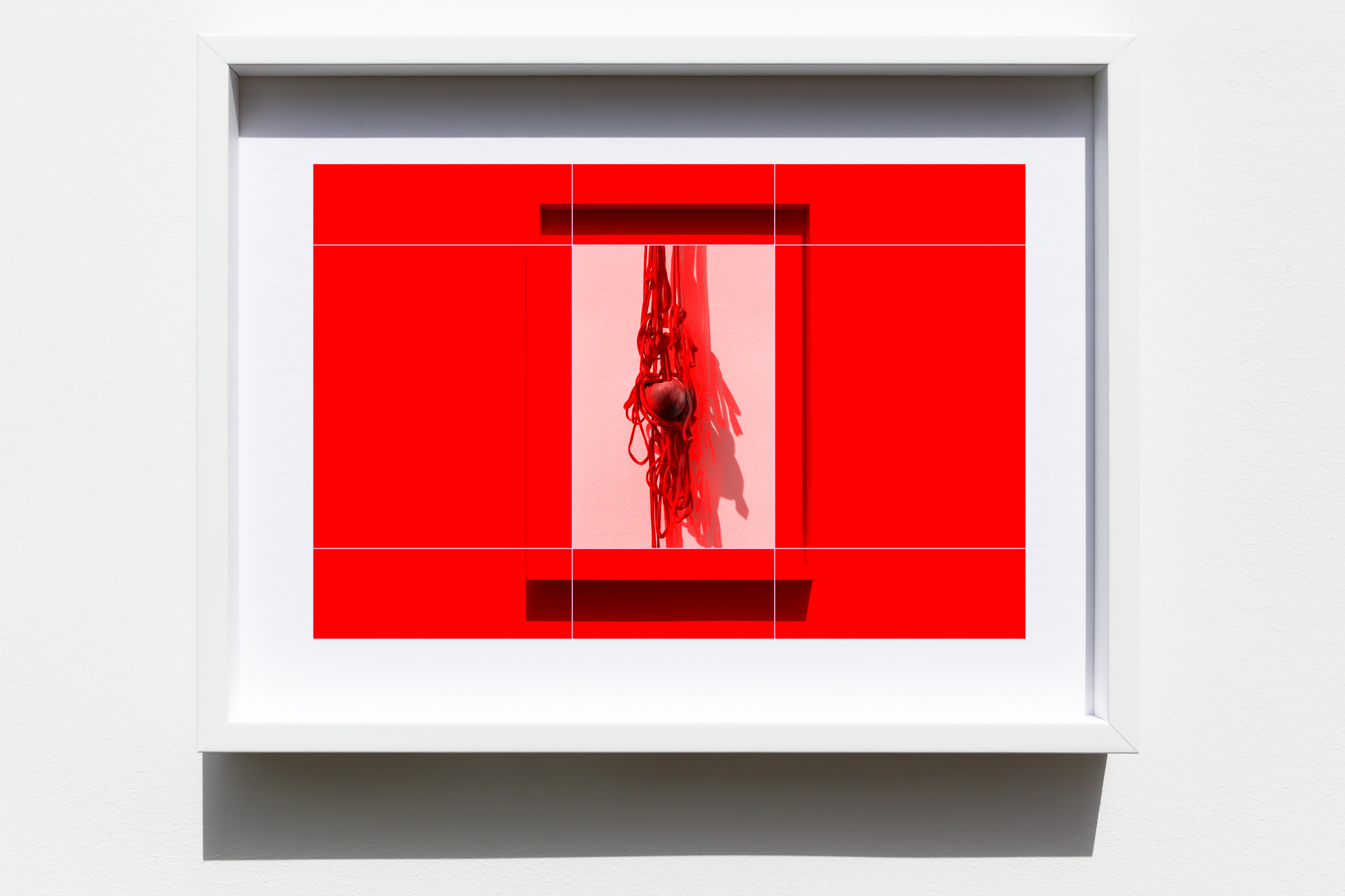

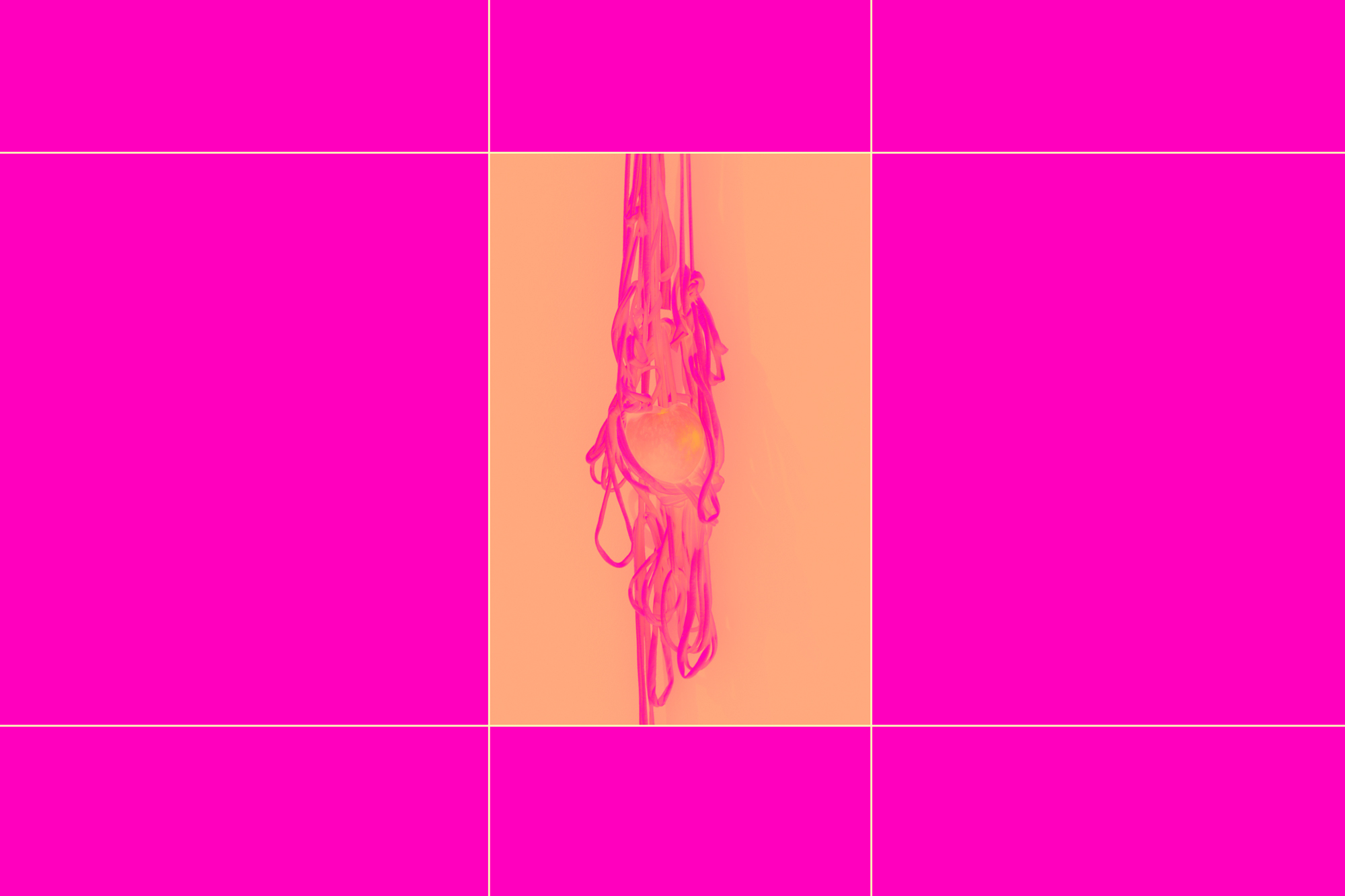

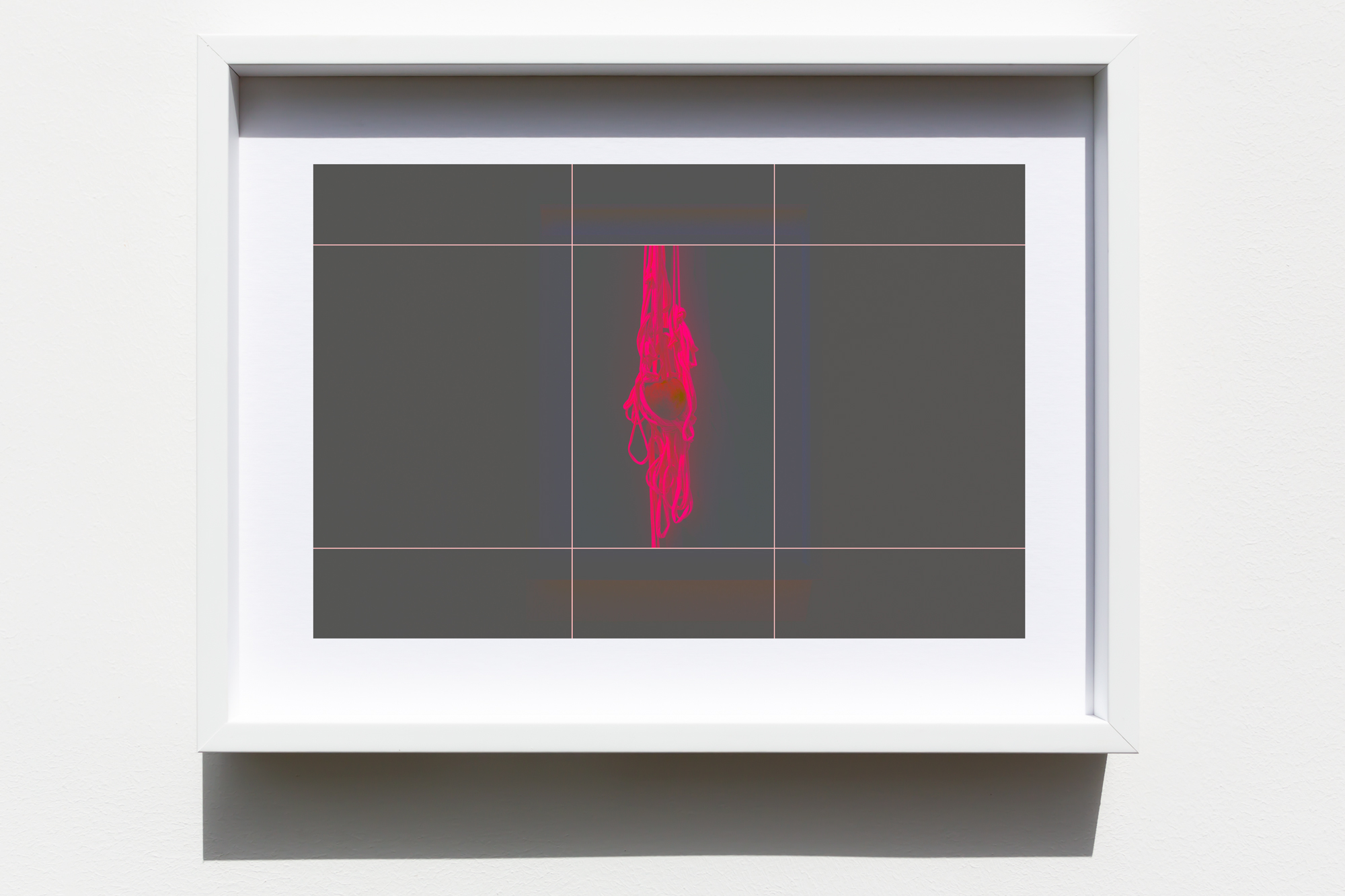

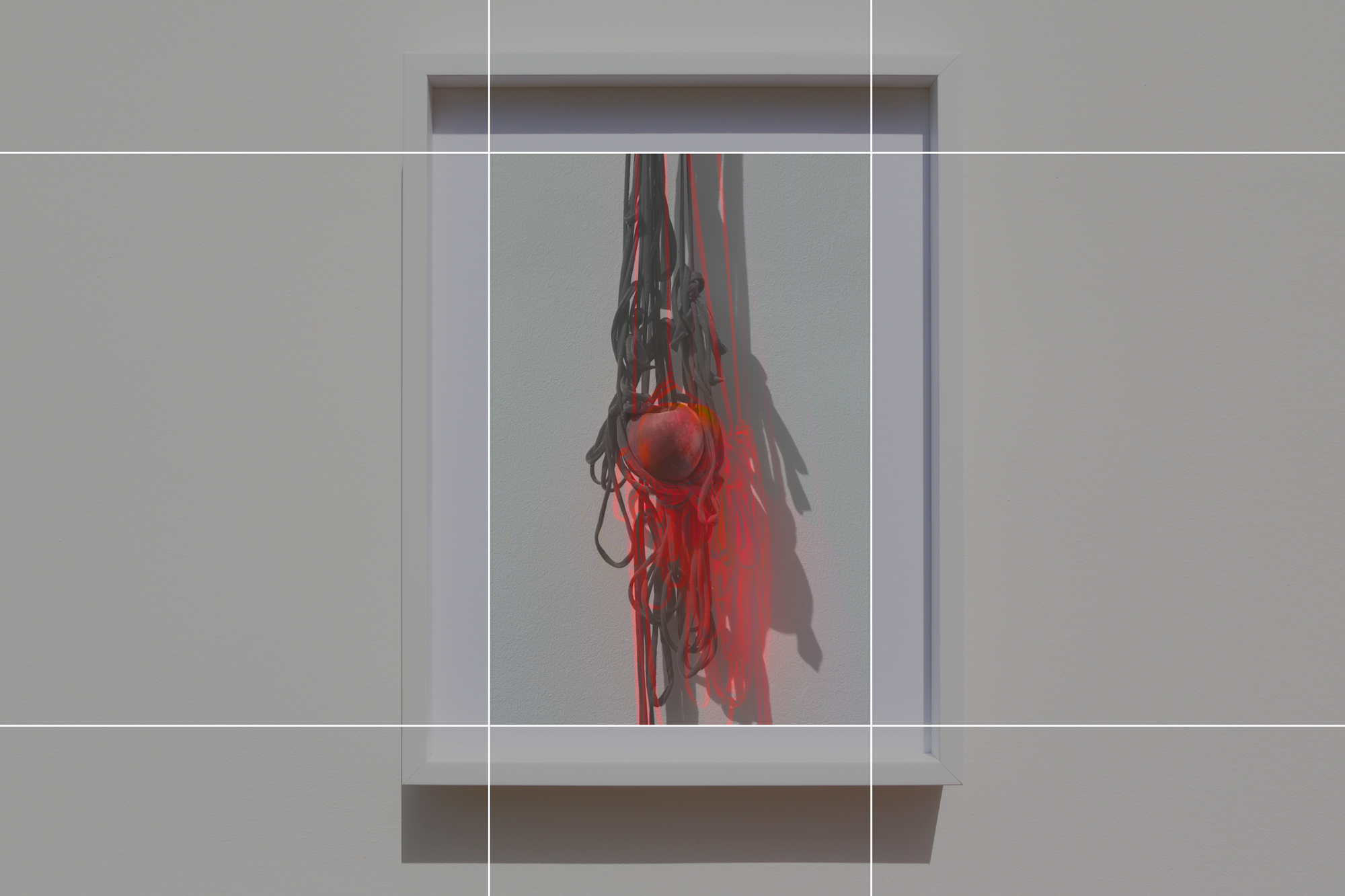

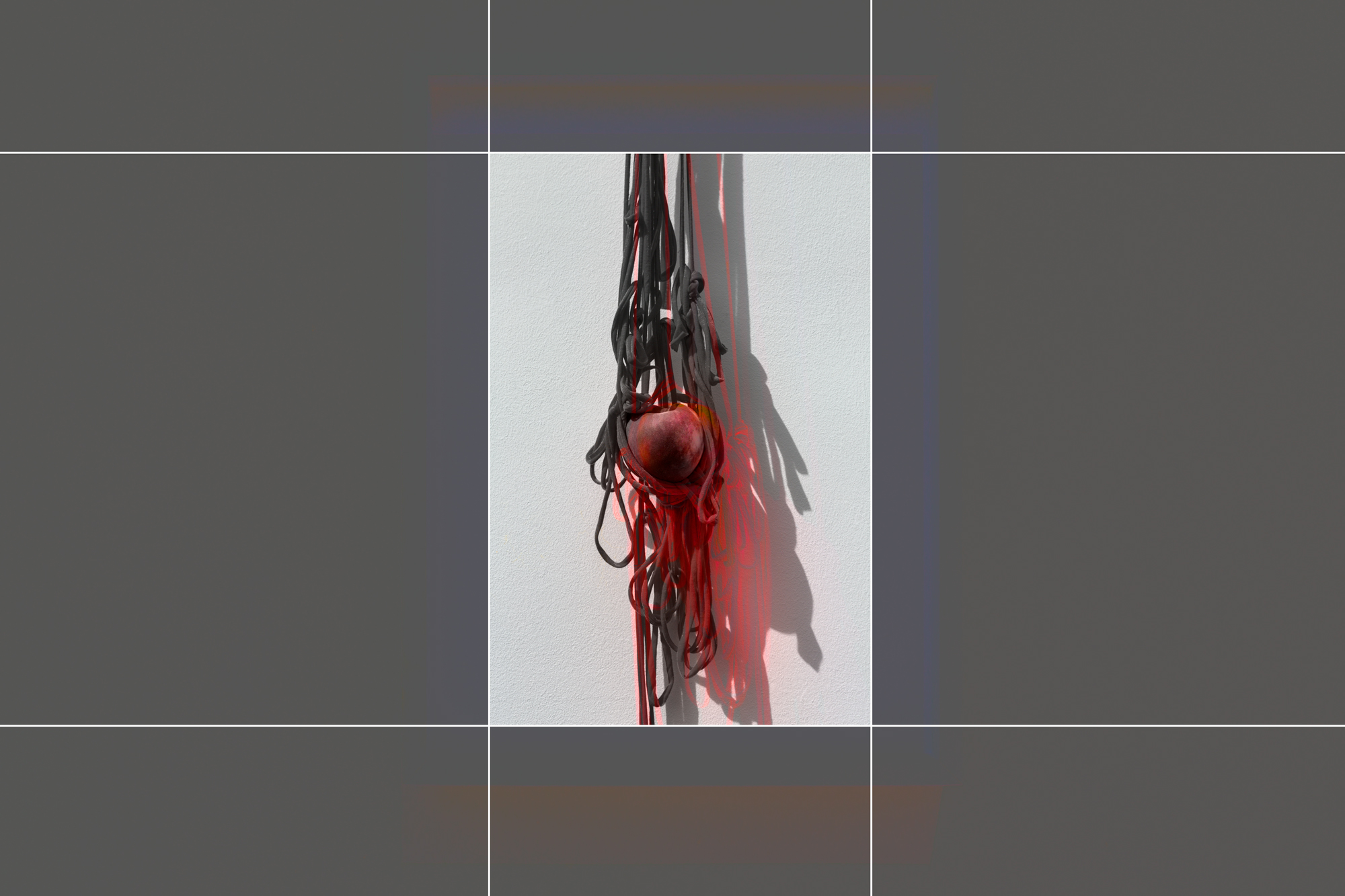

Orthós is the section dedicated to the fruits of labor in a matriarchal context, in which, with no man’s bidding, earth’s bounty was produced. The works of art engage with almost lost ideas of food production which are based upon symbiotic relationships and not solely on the greed of production. The harvest is the celebration of a moment that can also be repeated in the future because nature has been taken care of and not trashed. The association and alliance between plants is retraced to horticultural practices that have almost but disappeared. Orthós is about what is rect and correct and the agricultural structures or boundaries drawn on the land in a Cartesian grid that define patriarchal structures of production and exploitation. The ethics of food and food production emerge from a vegetable patch that is a work of art and — as innocuous as it may seem — challenges at the core the structures of contemporary Western democracies.

Image Captions: