“[…] ED IO VIDI NELLE NOSTRE VALLATE CRETINI CHE ALLA LUNGHEZZA DEL CRANIO, ALLA SPORGENZA DEL MUSO, ALLA GROSSEZZA DELLE LABBRA E PERFINO ALL’OSCURAMENTO DELLA PELLE PAREVANO NEGRI MALAMENTE IMBIANCATI.”

L’UOMO BIANCO E L’UOMO DI COLORE, CESARE LOMBROSO

Le Schiavone is one of ten sections of Lanfranco Aceti’s installation titled Preferring Sinking to Surrender which was conceived by the artist for the Italian Pavilion, Resilient Communities, curated by Alessandro Melis for the Venice Architecture Biennale, 2021. The ten sections are: Tools for Catching Clouds; Preferring Sinking to Surrender, Part I; Preferring Sinking to Surrender, Part II; Sacred Waters; Le Schiavone; Orthós; Seven Veils; Signs; Rehearsal; and The Ending of the End. These sections, singularly and collectively, create a complex narrative that responds to this year’s theme How Will We Live Together? set by Hashim Sarkis, curator of the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale.

The works of art — realized as a series of performances, installations, sculptures, video, and painting contributions — are part of the installation at the Italian Pavilion from May 21, 2021, to November 21, 2021, the opening and closing dates of the Venice Architecture Biennale.

Labor and the diminished social value of laborers is the element that characterizes the works of art in Le Schiavone. These new artworks by Aceti deal directly with dirt, labor, and becoming dirt. The artist makes use of a series of symbols to entrench women’s manual labor in the long history of art moving beyond the sexualized pornography of the patriarchal and classist gaze. Women’s identification with the definition of Schiavona in Italy places them in a specific rung of the social ladder: at the very bottom of it. These are women that labored — selling their bodies for work in the fields or survival — to ensure that their families and progeny would cling to life. Being directly associated with dirt and the lowliest labors makes them dirty and reduces them to the level of dirt. It is a process of reduction and encrustation that denies these women any role in the patriarchal state. They are not mothers, tainted as they are by the shadow of a sexually improper lifestyle typical of all destitute women; they are not workers, because their jobs are so abject that cannot be acknowledged, even if socially necessary, by the patriarchal rhetoric of the nation-state; and they are not women, because their lowly status does not make them beautiful or appealing but rather feral, wild, and savage. It is these women — seen as harpies, witches, and crones — that the works of art acknowledge, bringing back their hidden instances to the fore as a reminder that life as we know it was built upon the effort that these women made, securing the survival of their families and their communities.

Image Captions:

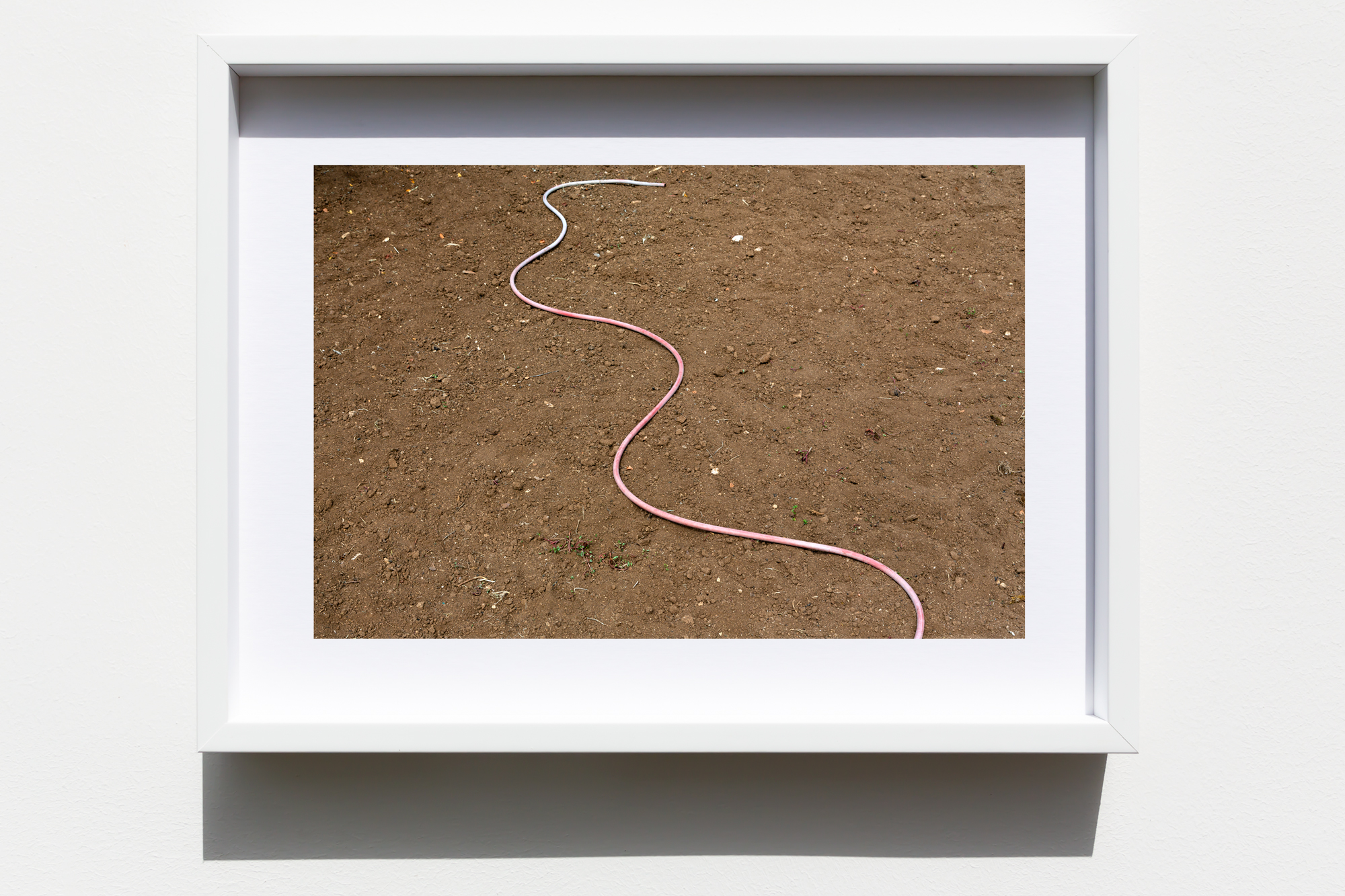

Lanfranco Aceti, The Insatiable Thirst of the Serpent of the Goddess, 2021. Ooze and soil. Sculptural installation. Dimensions: 20,000 cm. Photographic print from the sculptural installation. Dimensions: 67 cm. x 100 cm.

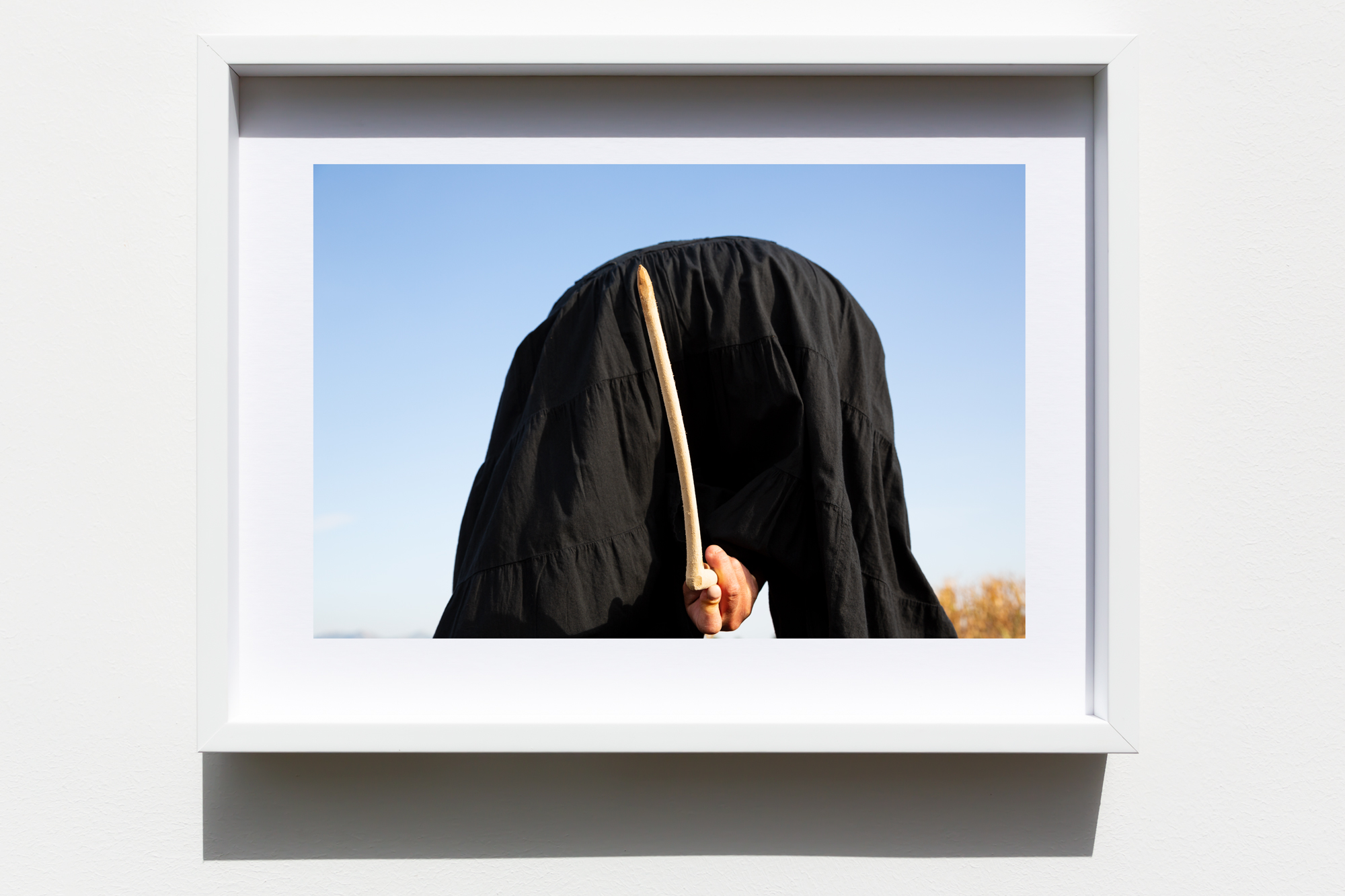

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.