Project Description

“JUSTICE TAKES TIME AND PATIENCE.”

LANFRANCO ACETI

Finding a stolen painting is always an exceptional event. Even more exceptional is the fact that this is a painting from the early Italian Renaissance. Lanfranco Aceti studies this lost masterpiece and reveals a different perspective about life, society, and politics outside patriarchal frameworks and cultural straitjackets. Justice in this case is made six hundred centuries later via a painting that brings back an understanding of pre-Roman and Roman customs and beliefs in Italy. The painting reveals that the Middle Ages were not the result of sudden and miraculous conversions to Christianity but a long suffered struggle that has continued until now. The painting laid bare, through nuanced symbolism, the complexity of censorship and the role that cultural resistance plays as a way of making visible alternative stories and histories that are antagonistic to the ones that are institutionally endorsed as dogmatic truths.

In 1993 I was working as a journalist in Italy and stumbled upon a painting during an interview with a notorious mafioso. To be truthful he was more of a financial consultant than a small level mafia boss. He left the details of socio-political events to be managed by others as far away as possible from his doorstep.

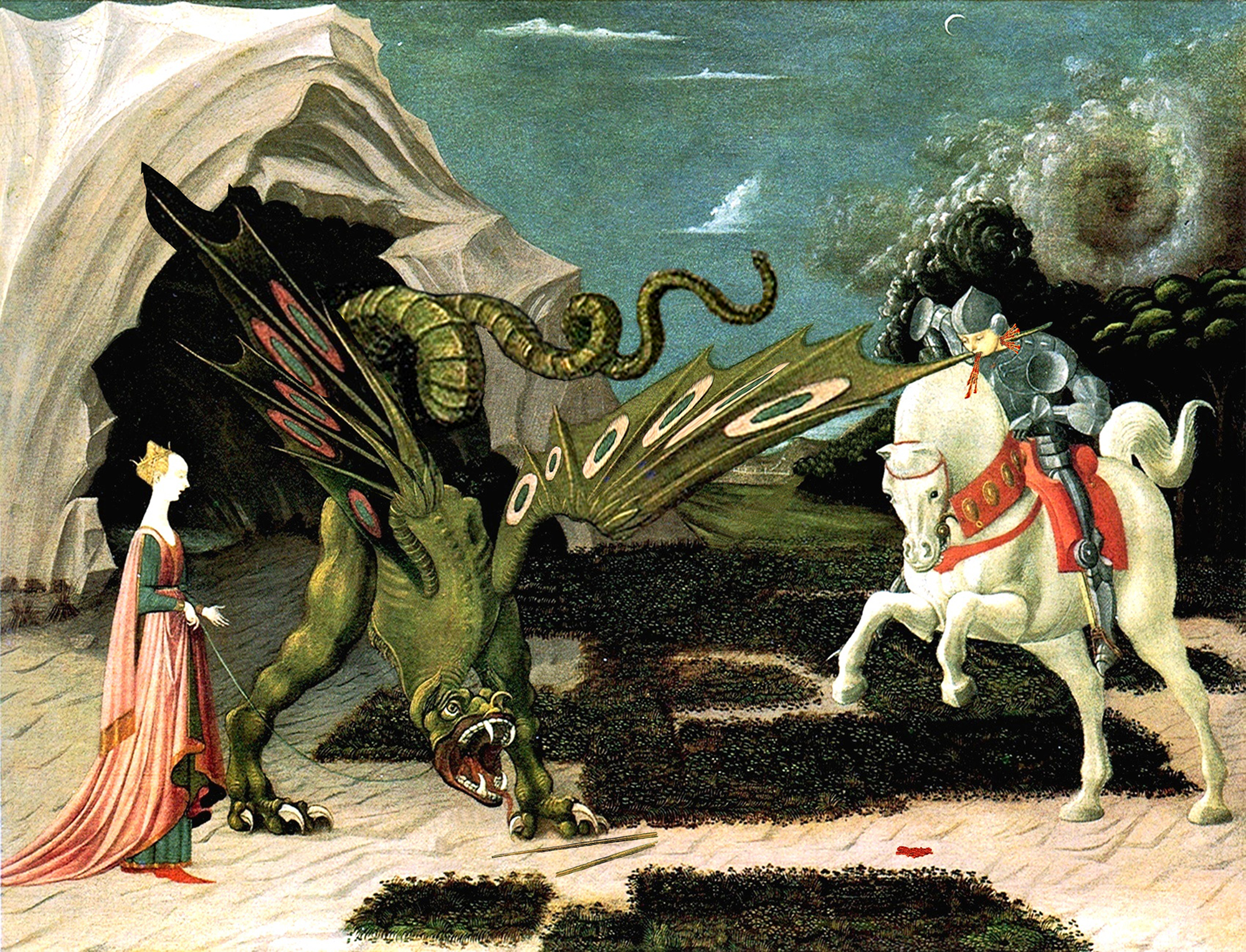

I always had been fascinated by Medieval and Renaissance art history, and, in particular, I had a special connection and penchant for Masaccio and Paolo Uccello. The painting I was staring at—in this large baroque palace in the middle of Rome full of frescos, decorative paintings, and tapestries—was rather unusual. I smiled thinking about the original, Saint George and the Dragon (c. 1470), that is hanging on the walls of the National Gallery in London. I immediately recognized that the painting was a work by Uccello. Nevertheless, it was not an exact copy of the original since the scene represented was rather different from the one I had studied in art history books and had seen in London. Whomever had painted it had enjoyed turning the story upside down. Saint George was no longer killing the dragon. The dragon was killing him.

My first instinct was to get close to the painting and look at it carefully. I doubted that a mafioso would have a painting by Uccello. Nonetheless, people have quirks and I kept smiling thinking of someone who had gone through so much trouble as to commission such an exquisite intellectual and material fake. The mafia is renowned for dealing in antiques, both fakes and real, and for using paintings as collateral, for exchanges, or as ‘safe money’ for a rainy day.

He had seen me smiling and shaking my head slightly while checking the recorder to make sure that all was ok.

“It is real you know,” he said. “It is not a fake.”

He said it seriously and as he did I looked at him and at the painting again. It did seem an excellent work. It had all the brush strokes seen in Uccello’s paintings. The colors, the structure of the horse, and the landscape were incredibly close to the canon. They actually ‘seemed to be’ the canon.

“May I get closer?” I asked politely. Being polite was the rule if one wanted to get out alive and not be slowly melted in a bathtub of acid.

There were several things that puzzled me. Why was he saying that it was an original when instead the story represented would subvert every possible religious canon of the time? Why someone would go to such a length to have an exact replica of the original only to alter its story so radically that it would become unbelievable and scream ‘fake’ miles away?

There was another possibility. And that was that the painting was real and for some reasons had been kept, throughout history, away from prying eyes. I could see why, since representing the defeat of a warrior like Saint George would symbolize the defeat of the Church, and its patriarchal history, at the hands of a woman wielding supernatural and preternatural forces. At the time the painting would have gained Uccello not a merciful bathtub of acid but much worse tortures at the hands of an ever more inventive Inquisition.

There were things about the painting that screamed at me and told me that it was an original. The colors were in amazing condition and that could have been explained by the fact that the painting had to be kept in the dark, both metaphorically and physically. Even in that moment while I was looking at it there was no sunlight that would reach it. It had been placed in the darkest corner of the room where the sun, even at its height in August and with all the windows opened, would not be able to touch it.

“Yes,” my host said. “It is as you guessed. We keep it well away from sunlight. I debated if to take it out of storage and hang it. In the end I decided that it was too beautiful to be kept in storage.”

I smiled and kept looking at the painting, mesmerized not any longer by the materiality of the painting but by its subversive narrative. It would represent the conflict between matriarchal and ctonian forces against the patriarchal impositions of Christianity and the erasing of Pagan cults and traditions that had stood for millennia across the Mediterranean.

“Who would have ever commissioned it?” I asked myself loudly, totally taken by the infinite historical possibility of what might have happened and why.

“Nobody knows, but there is a story about it,” said my host. “It recounts that Saint George, one of the military saints, attacked a princess who was guarding the tree of life with her dragon. Saint George and his army were defeated but a larger army arrived and destroyed the entire population. The princess was raped and then impaled on a spear and carried and exhibited as a warning to all the surrounding villages. The few survivors, among them was the younger sister of the princess, reached Rome and for almost two millennia have been waiting for their moment of revenge. One of their descendants commissioned Uccello, who had portrayed the legend of Saint George, to create this painting as a reminder of their ancestors and their own lives’ mission.”

I was taken aback by the story and wanted to ask something else, when my host pointed to the chair that I had left. “Shall we go on?” he asked.

That was the last time I saw that painting and since then I was left with the doubt of its authenticity as well as with the curiosity of the legitimacy of the story that was recounted. From time to time I have looked at historical facts of the military saints of the Church, at the remnants of the clashes between fanatics, and at the pace of history as one that covers and uncovers, hides and deceives.

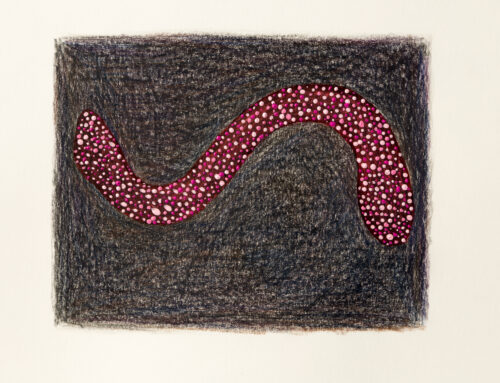

Recently, during the pandemic of 2020, I have decided that this painting deserved to exist outside of the darkness in which it had been plunged. I was commissioned to create a copy of it, which now is in a private collection. I titled it Iustitia Fecit (I Made Justice) because I wanted to bring justice to what might otherwise have been considered an irrelevant historical fact. Unfortunately, history is made of the unheard plights of irrelevant historical facts, all sacrificed in the name of some ideology or superior reason.

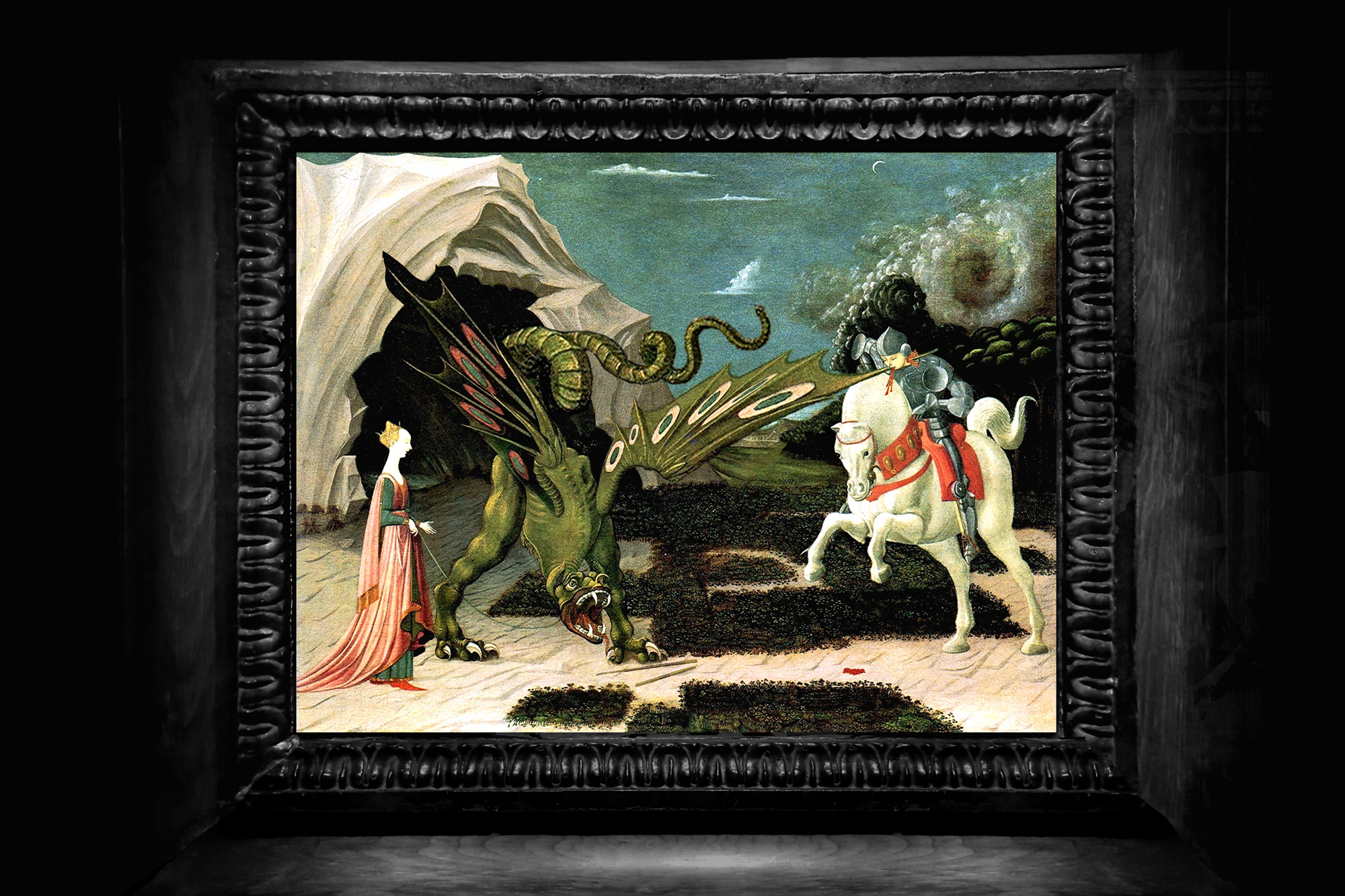

Today, this is the only image available of the original painting. I have never seen it since. It must have disappeared somewhere, hidden in a Swiss bank or in an art storage facility, waiting to be traded. The painting does not exist but as a joke and a memory, shrouded in mystery and darkness, unlike its owner who was able to accumulate great wealth and political clout and bask in the sunlight of fame and glory. Sic transit gloria mundi.

Image: Lanfranco Aceti, Iustitia Fecit (I Made Justice), 2020. Oil on canvas. 60.15 x 70.56 cm. Private collection.