“Even if you encounter opposition, have conviction and finish what you start. People in the end will understand.”

Kotoko Wamura

Living After the Apocalypse is a curatorial proposal I conceived and developed when I was invited to submit a conceptual framework for an art and architectural biennial in 2011. While I was writing and preparing the proposal an earthquake happened in Japan and the city of Fukushima and its surrounding areas were flooded by a Tsunami and covered by the radioactive fallout following the collapse of a nearby nuclear plant. Certain that the events would make my proposal even more relevant — floods, fires, and disease were and are projected to increase due to environmental stability — I kept on working and tried to explain what the title meant, what the biennial would have been like, and what type of events would take place.

The proposal was not selected.

I have enough experience to understand that work is never wasted, at some point or another with enough time somehow my themes or approaches will become relevant or someone will acknowledge their importance.

The focus of the proposal is incredibly relevant today, ten years later, and will continue to be relevant in years to come. The blind and self-centered optimism that has characterized the past fifty years, the arrogance of anthropocentrism, the certainty that this is life and not a fragile instance of it, appear to have continuously led human ingenuity to the point of collapse.

Granted that the theme I had chosen for the biennial was complex, I did not feel that there was any pessimism in it — although this was one of the reasons for its rejection. On the contrary, I felt that there was a positive approach in seeking solutions and resolutions to humanity’s problems. Using technology and ensuring access to it, changing and shaping behaviors through design, altering and understanding the roles of art, architecture, and engineering not as knee-jerk responses to disasters but as tools able — if not to prevent possible disasters on a global scale — to at least allow communities and people’s standards of living to continue after the apocalypse is, in my mind, the best way of acting positively and proactively. The problem was the premise upon which the theoretical and philosophical constructs of the biennale were based: the acknowledgement of the incapacity of humanity as a whole to alter its course. Therefore, the obligation to accept — at least in hypothetical terms — the inevitability of disaster.

The concept was simple: what if we have run out of time and it is no longer possible to stave off disaster? Shouldn’t we be using art, architecture, design, technology, and scientific thought to reimagine and redesign a) the way we live and b) to adapt to the new landscapes that we might be forced to live in? The possibility that something might happen, or the certainty that it might happen in a not too distant future, does not spur humanity to action. The irrational greed of today, under the disguise of economics, trumps even future losses. Even when it is economic folly not to prepare for the future by sacrificing a little today in order to avoid major economic losses tomorrow.

Living after the apocalypse was the main focus of the proposal. How can we continue to keep on living by retaining the same standards of life, and perhaps even try to improve them in the midst of disasters? Is it possible to reduce the impact of a catastrophe to zero or even take advantage of it? Can we reimagine the disaster in financial terms as an opportunity for gaining knowledge, expertise, and also financial remuneration since research has its costs? This was a tangential point to the proposal but one I had to make since the only way to attract sponsors is to show them how they can monetize any given situation, and I thought that this would interest international brands in architecture, design, and engineering. I had not calculated the extent of the myopic perspective of most CEOs. In their terms as well as in political terms, preparing for a disaster today that might happen ten or fifty years later is a useless endeavor if considered in the context of contemporary short-term approaches.

These days I believe the curatorial proposal I wrote ten years ago might have a slightly different reception.

In the proposal the concept of living was meant as continuing to go about one’s business without much disruption or with no effort. It was a way of considering contemporary dystopia not as an unfathomable accident but as a certain disaster that would happen sooner or later in the timeline of one’s existence. Philosophically the proposal would also examine the inability of humanity to act collectively and outside the remits of greed. It would pit the local against the global, to argue that the survival of the local against global interests would represent the best chance for human survival and the preservation of a nation state. Therefore, the concept of living was juxtaposed to the concepts of surviving, scrounging, stripping, lingering, sustaining oneself, clinging, pulling through, and all the other synonyms that would imply a basic existence.

Living After the Apocalypse was meant to find tools and ways of living in harmony, living with comfort, living with joy, and living in symbiosis with the natural environment. The proposal had at its core the following idea: let’s assume that global warming will happen, nuclear disasters will plague the earth, earthquakes and tsunamis will strike with greater force and more frequently, and that pandemics are normal, and let’s see what we can invent to redesign public and private spaces accordingly and what role art can play as a cultural and creative human endeavor in this context. Let’s see if we might continue to live without mass culling, the solution of most disaster movies and some ‘politicians’ over the centuries, but instead with a gradual reduction in population growth in order to save resources.

Today, at the time of COVID19 and an accelerated climate change bringing increased meteorological destructions, it would have been rather useful to have a reimagined structure of our society with emergency response technologies ready to be deployed. For those venture capitalists out there, who do not venture very far, these response technologies could be sold to anyone who might want them and could afford to pay for them in their dire moment of need. The current gains of the pharmaceutical industry show how profitable investing in ‘future disasters’ can be, no matter what they are: flooding, fire, earthquakes, tsunamis, or diseases.

The possibilities for creative ideas and technological deployment are immense, particularly if we can reimagine social interactions, architectural spaces, and scientific approaches. If it could be possible to develop small peripheral communities as test beds of survival techniques and methodologies, the sharing of their accumulated knowledge might be able to provide opportunities for the survival of a form of centralized state. Nevertheless, this approach clashes with the need for bureaucratic control and the fear of change. Autonomy has always been considered an enemy and smallness something to be overcome in favor of bigness and centralization.

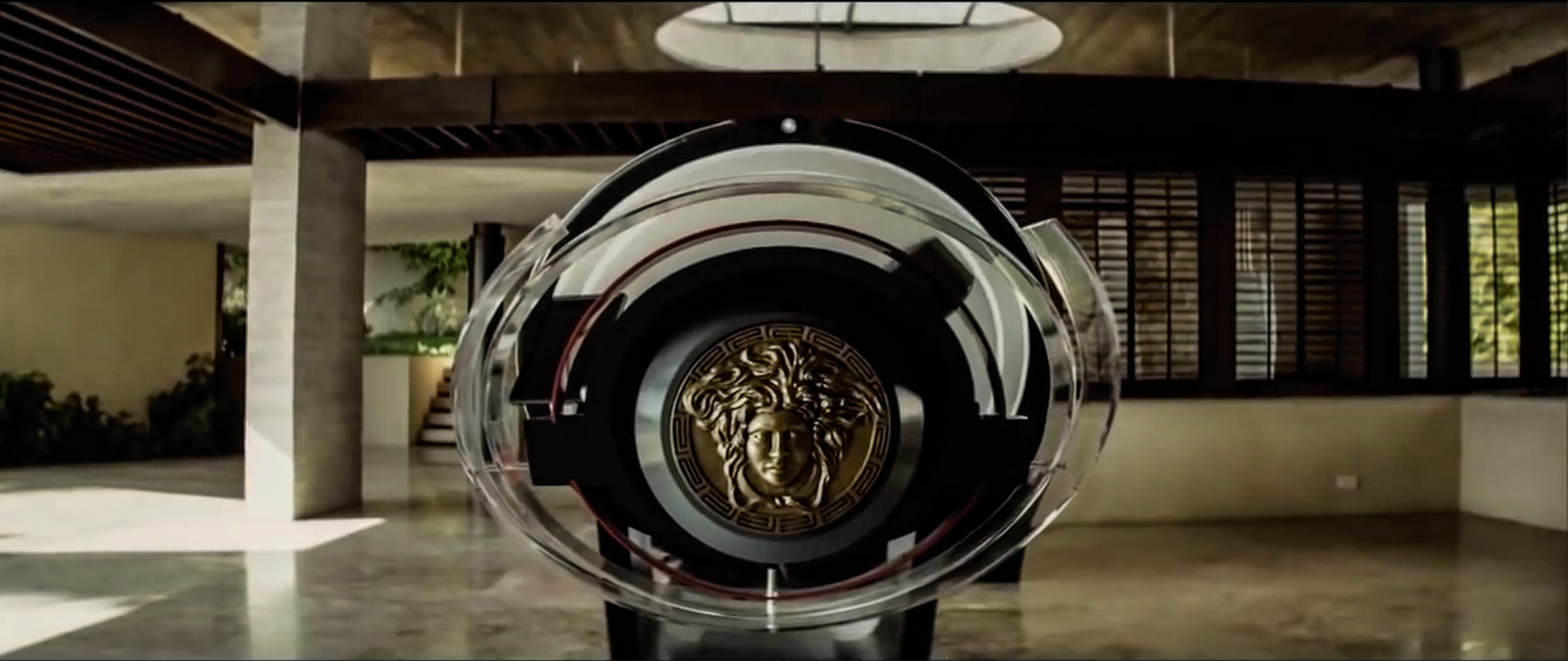

Technological examples of what could be an alternative to large architectural buildings for hospitals could be offered by the concept behind the SciFi medical pods, the best of which is from Armadyne, realized for the movie Elysium (2013). The medical pod, for those who are fashion conscious, is stylishly designed by Versace. These pods could be deployed in public spaces.

The lack of preparedness that was exposed by the Covid19 worldwide events or by the Fukushima Nuclear Plant’s collapse open up larger socio-political questions that both as an artist and curator I feel I should ask:

- How long will it take populations to understand that there is and there always will be a need to prevent disaster and that, particularly now, politics should change?

- Is it not yet clear that the European Union project has to either evolve in a fully functional federation or disband, since in its current form of selfishly absorbed nation-states it is unable to respond to the challenges of the twenty-first century?

- How long will it take US citizens to understand that public services cannot be privatized because the private sector’s short-term interest in cashing in does not align with the public’s general interest to ensure the development and success of a nation?

- Also, will nation states ever be able to convince their bureaucracies that local autonomies and local specific needs are not in direct contrast with an idea of a centralized nation state?

- And finally, I expect that many art organizations will start now to ask what is their role and the role of the artist in a time of pandemic, social, financial, or climate crises. Will art organization be able to develop programs of research and cultural development rather than superficially responding to fashion fads?

The last question is one that I can answer: the mandate of art institutions and of the artist should be that of having the courage to shape cultural and aesthetic agendas ahead of time by anticipating the future and presenting projects that are challenging, unusual, and thought-provoking and able to provide the viewer with multiple scenarios of aesthetic thinking and knowledge. The role of art institutions and artists is certainly not that of running after fashions, corporate dictates, and pandering to and entertaining audiences, like most art organizations have done in order to demonstrate their success. A different aesthetic model — one that is more in tune with and more inclusive of contemporary social, financial, and environmental issues — should be put in place.

In my biennial proposal, Living After the Apocalypse, I wanted to institute a prize named after the former mayor of Fudai in Japan, Kotoko Wamura, who out of sheer vision, memory of previous historical events, and unwavering foresight initiated and supported the construction in the 1960s of a 50 foot sea wall that was able to withstand the force and waves of the 2011 tsunami. His vision, at the time, was considered a folly. Nevertheless, he completed the construction of the wall, saving the lives of 3000 people in 2011. Sadly, he was no longer alive when his foresight saved the very people who had considered him mad and ostracized him for the amount of money that he spent on a wall that they thought useless. This proposed prize conceived for the unrealized biennial, Living After the Apocalypse, was to be awarded to the most daring and visionary idea coming from artists, architects, designers, and engineers.

LIVING AFTER THE APOCALYPSE (The Original Proposal 2011 © Lanfranco Aceti)

Living After the Apocalypse started from the assumption that humanity is no longer able to avert environmental catastrophes: harsher weather conditions, rising sea levels, pandemics, earthquakes, tsunamis, and human made disasters. Therefore, how could we redesign, build, and create communities that are able to survive the collapse of a centralized and inept (at best) system of management of services and production?

The proposal for the [name withheld] biennial, Living After The Apocalypse, embodies a message strongly focused on human agency, following cultural traditions of pro-active and farseeing engagement, in opposition to visual imageries of mere survival — as in traditional dystopian visual representations that only offer and fetishize visions of collapsed and dysfunctional architectural, urban, and social landscapes.

The curatorial concept for the exhibition and the conference, the two main outputs of the biennial, proposes to launch an international message of positivity, empowerment, and human agency. By stressing the word ‘living’ the exhibitions, conference, and art/cultural events will place emphasis on contemporary art, architecture, design, and engineering as the key factors that — by envisaging the future landscape and focusing on retaining living standards in the face of contemporary crises (economic, social, political, and environmental) — will make the difference between succumbing to disaster, mere survival, and living after the apocalypse.

The biennial will launch the message that foresight, advanced thinking and planning, research, and creativity can lead the way in pre-empting future crises and developing new architectural models, service systems, cultural frameworks, aesthetic thinking, and technologies that can ensure living standards even after the apocalypse.

The biennial will reject the idea that the apocalypse is a disaster that communities have to succumb to or that cannot recover from. It will launch a series of initiatives (research groups, project incubators, exhibitions, and cultural events) that by uniting the creativity of contemporary arts, architecture, advanced technology, new scientific thinking, and innovative social models can provide alternative solutions to the traditional representations of inevitable disaster and doom.

The biennial will acknowledge the foresight and planning of visionary artists, architects, designers, and engineers who are able to imagine and present a future for a quality of life in spite of pending theories of doom. The biennial will seek to empower these visionaries and at the same time acknowledge the possibility that humanity, as a collective global force, will not be able to avert the current environmental, social, economic, and political crises that mark the current post-postmodern world. Therefore, those who can should think, invent, create, and act.

Focusing on the spirit that characterizes the hosting country and allows it to present itself as a safe haven, the theme of this curatorial proposal is to present the hosting city and the hosting country as the locus where art, architecture, design, science, media, and technology meet in order to deliver a positive message of future sustainability and resilience despite and in spite of current global representations and incidents of doom and conflict.

Credits

The images in the post are from: Elysium, directed by Neill Blomkamp, 2013.

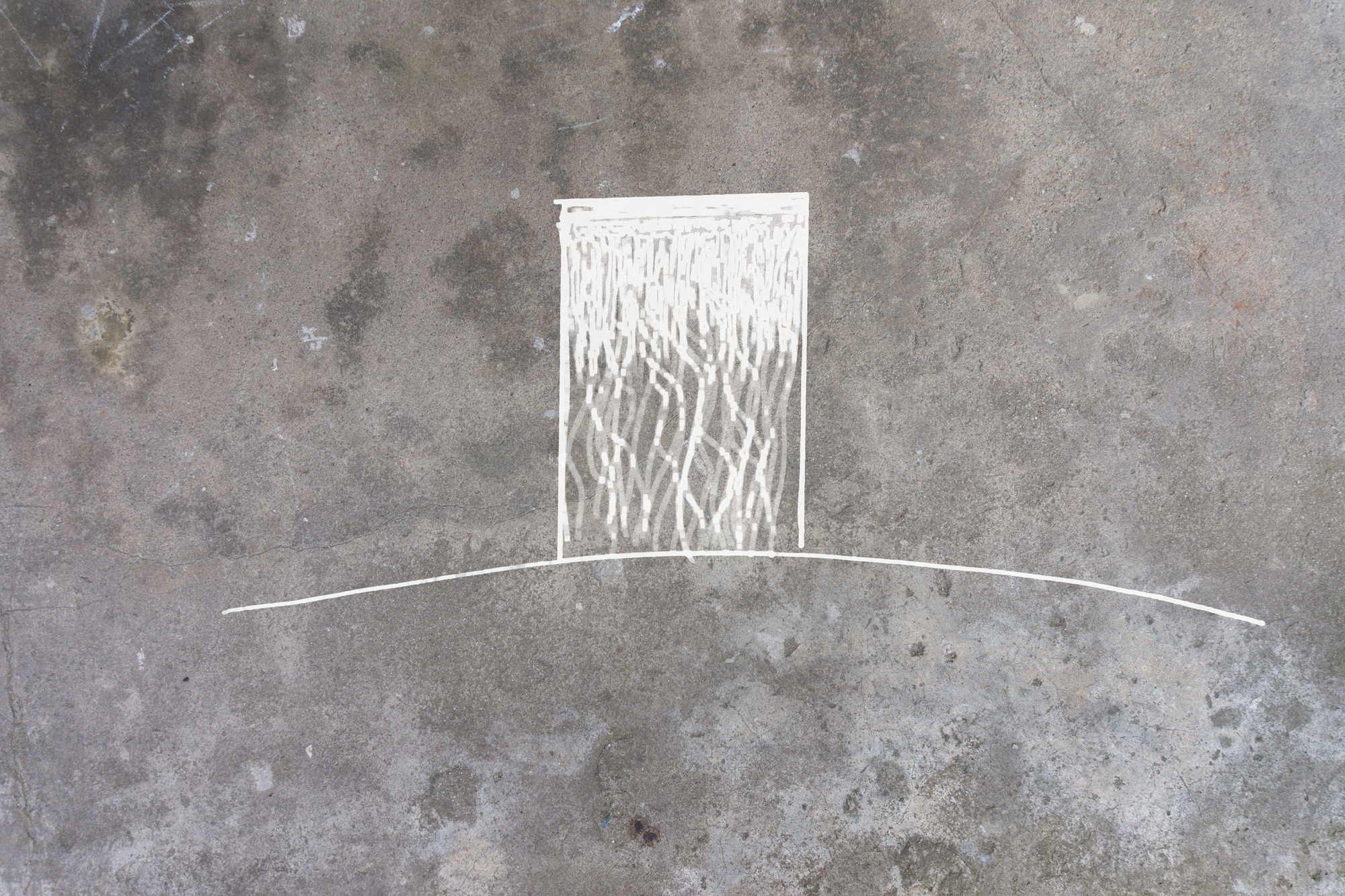

The images in the slider are two sketches of Anemone: The Data Gate, Lanfranco Aceti, 2011.