“BLESSED ARE YOU WHO SPEAK ABOUT LIFE AND DEATH WITH THE FIRST WORDS THAT COME TO YOUR LIPS.”

THE HAWKS AND THE SPARROWS, PIER PAOLO PASOLINI

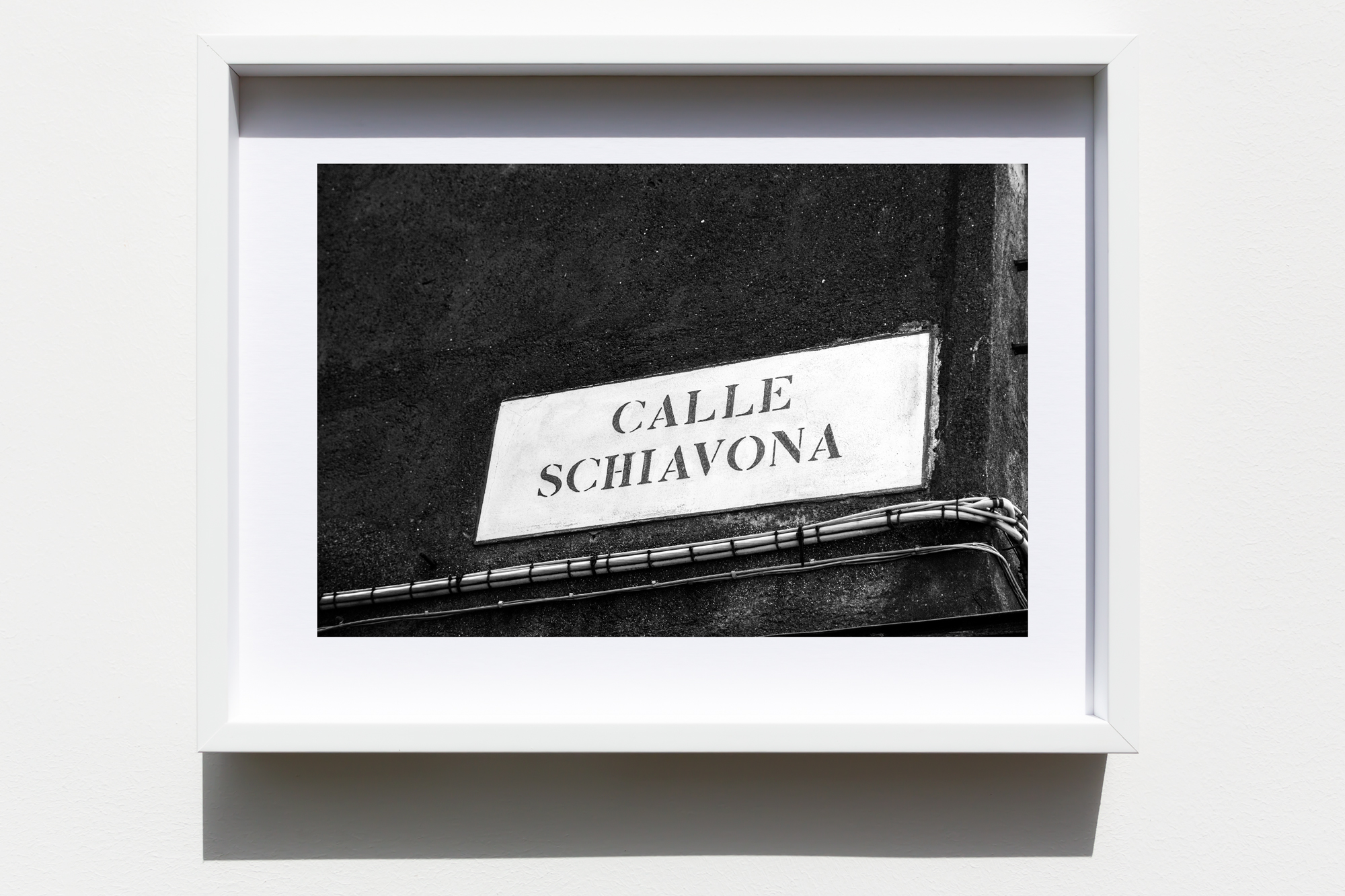

Sacred Waters is one of ten sections of Lanfranco Aceti’s installation titled Preferring Sinking to Surrender which was conceived by the artist for the Italian Pavilion, Resilient Communities, curated by Alessandro Melis for the Venice Architecture Biennale, 2021. The ten sections are: Tools for Catching Clouds; Preferring Sinking to Surrender, Part I; Preferring Sinking to Surrender, Part II; Sacred Waters; Le Schiavone; Orthós; Seven Veils; Signs; Rehearsal; and The Ending of the End. These sections, singularly and collectively, create a complex narrative that responds to this year’s theme How Will We Live Together? set by Hashim Sarkis, curator of the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale.

The works of art — realized as a series of performances, installations, sculptures, video, and painting contributions — are part of the installation at the Italian Pavilion from May 21, 2021, to November 21, 2021, the opening and closing dates of the Venice Architecture Biennale.

With the element of water, as the primordial element of life and death, Aceti opens this section of works of art. The inspiration came from the complex matriarchal cultural history of a place, the Valley of Canneto, and the sacrality that has characterized it across millennia. Sacred Waters deals with the reduction into mucilage of the locus in which resided the Magna et Nigra Mater, the Goddess Mephites, Cybele, and now the Madonna Nera di Canneto. The artistic exploration is a journey in which the right to access to water, to the sacrality of anthropological rituals, and to a model of matriarchal society and living continue to battle against the greed of contemporary capitalism and the selling of ‘ the family silver’ in the name of economics for the few. It is a clash between the last inheritances of agricultural existence, food survival, and an understanding of life that retreats in front of a post-postmodern onslaught. The sacred waters retreat but, through their absence, speak of popular beliefs and a mythological realism that will breathe new life into the ira deae (the rage of the goddess).

Image Captions:

Lanfranco Aceti, The Memory of Water, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Run, Run, Run, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Flushed, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Flushing, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, To Flush, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, re-mors, 2021. Gif animation.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.

Lanfranco Aceti, Untitled, 2021. Photographic print. Dimensions: 100 cm. X 67 cm.