Project Description

“YOU CAN’T SAY THAT I HAVEN’T TOLD YOU SO.”

LANFRANCO ACETI

Contemporary frameworks of capitalistic exploitation are all the rage when things go well. But what happens when contemporary western societies in general, and an unruly country like Italy in particular, are obliged to show unity for the sake of the common good so much belittled over the past thirty years in favor of necropolitics, selfishness, and greed? What happens to ‘i furbi’, the astute ones, ready to pass on everyone’s dead body for their own personal gain?

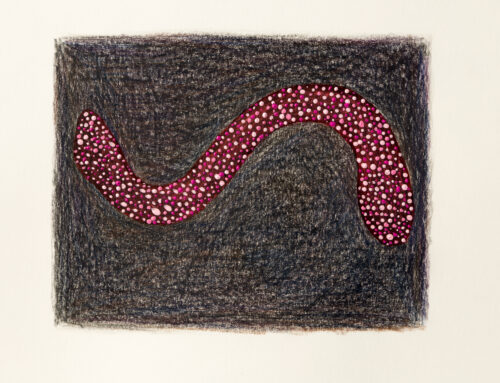

Do Not Touch Me! is a series of portraits and installations at the time of pandemic. They recount the complexity of the deconstruction of contemporary society and the consequences of post-modernity on the social ability to face up to global challenges.

This analysis is made through the lens of a small town in Italy, which, despite its smallness and narrow-mindness, nevertheless is able to represent all of the different facets of living in the twenty-first century, at a time in which post-democracy and post-citizenship are now rooted in our everyday unethical existence and social mores no longer hold together the fabric of society.

The works of art challenge both notions and representation of equality, normalcy, and bourgeois living. Italy is no longer in a condition of normalcy but is spinning in a socio-political trajectory of conflicts, radical change, and financial crisis. The present pandemic has represented both a moment of reckoning but also a moment that has revealed, if it was ever necessary, the divisions within the country between law-abiding citizens and ‘i furbi’, those who flaunt the laws and selfishly abuse the system for their own short-term advantages.

It is also a moment in which the EU has reminded the country that its existence within the European framework is fragile at best and that the country geographically is the threshold of Europe for vast territories: Africa, the Middle East, and the Far East. This should perhaps remind Italians, who have in large numbers embraced racism as a political tool, that they belong to the extreme northern hemisphere of Africa and not to Europe.

Italy’s current inability to see and feel its role within the world and within its own geography and historical landscape is due to an inherited recent cultural history that necessarily wants it anchored into Europe, when instead it should seek its role within the Mediterranean and from there across the multiplicity of cultures, races, and religions that historically made up its aesthetic, cultural, and intellectual strength.

The artworks appear to respond to the pandemic but—while apparently addressing the pandemic itself—they question the role of motherhood, socio-political failures, intra-national and interracial relations, and other fundamental cultural inheritances that have been post-modernized but never really absorbed or understood. Italians were in the 1960s emerging from a global landscape that saw them outside the racial configuration of Europe and the Anglo-Saxon world. The Italians never belonged to it, not fully, nor were accepted, not really.

Masks are no longer available to stave off the pandemic and migrants and Italians alike now share in the common destiny of abandonment by culpable and inept political elites at local, national, and European levels. Therefore, they are forced to invent, test, and share strategies of survival. Masks can be made into signs of defiance, signs of blindness and obtusity, signs of betrayal and abandonment, signs of shortsightedness and idiocy, but also into signs of revenge and dues to be paid.

Whatever the results of this deadly virus (or strong influenza according to alternative theses and perceptions of reality), another understanding of citizenship will be born from it. This is an understanding that will not be rooted in old and frayed categories of nationalism, capitalism, and state. It will not be conditioned by political and social categories that have failed to deliver the very basic of human ethical values, obliging the mind to envision ways to overcome dramatic scenarios of survival. Citizens had to stave off notions of the elderly’s death that has been presented as an acceptable cost in capitalistic ethical terms. The scar of this pandemic, real or fictional that it may be, will leave a renewed self-understanding of a people, of who the Italians are as human beings, but also of who we are and who we deal with in this world of economic metrics and youth as absolute value. This understanding of one’s role as family member, as citizen, and as people in relationship to the surrounding geo-political space will generate, in the view of the artist, a new brutal form of populism, one that will exact vengeance by shedding the hypocrisy of notions of democracy that promise but never deliver, and will unveil the reality of existence in the twenty-first century globally as well as in Europe, Italy, and in a small mediocre town called Cassino.