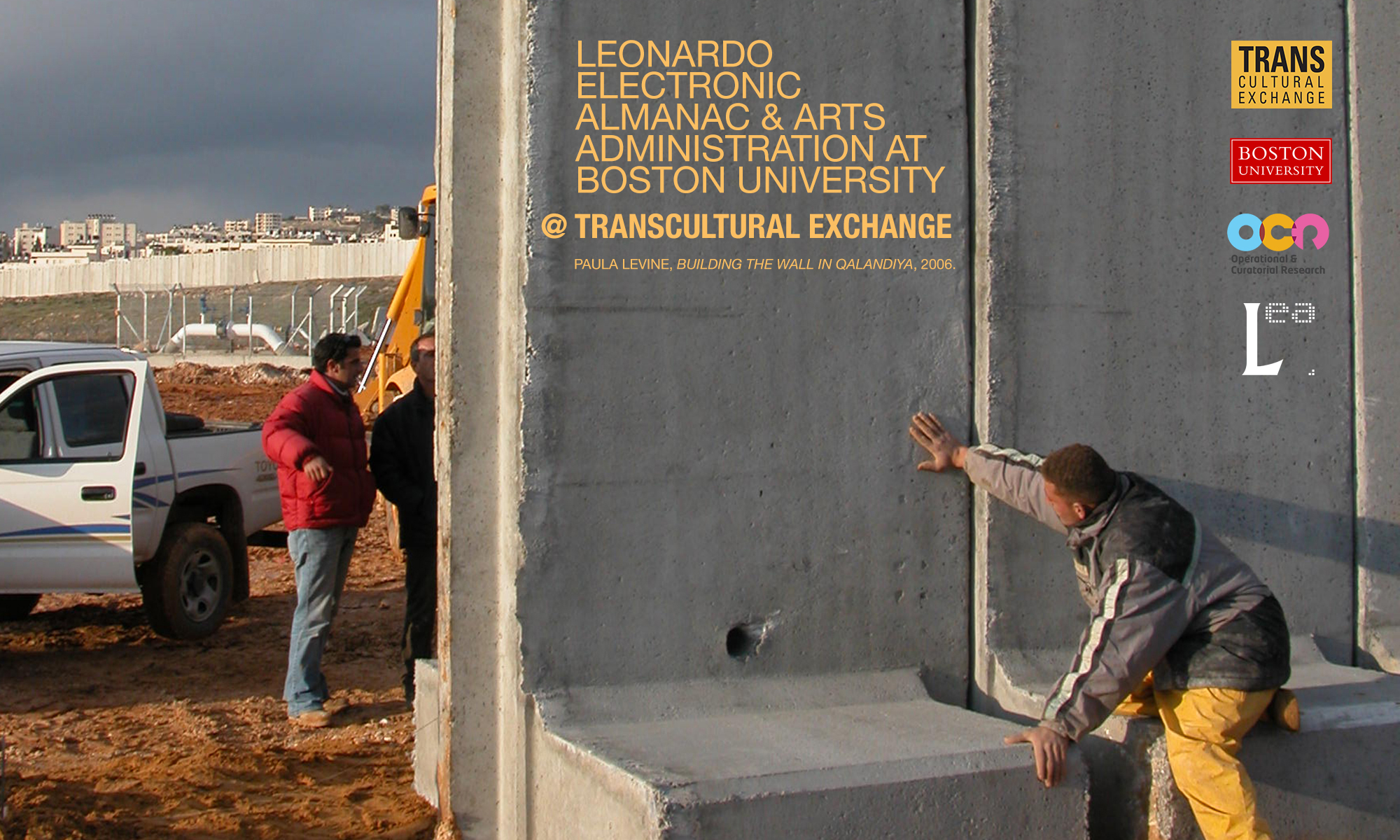

“Bashed on the Head: Global and Local Tensions in the Life of an Artist,” is the new essay that I am writing for the TransCultural Exchange conference at Boston University organized by Professor Mary Sherman. The essay, which also gives the title to the panel, will be a moment of conversation between esteemed colleagues and the audience. The panel location is: Boston University, George Sherman Union, 2nd Floor, Metcalf Hall, Small Hall – Thursday, February 25, 2016 3:15pm – 4:45pm. Moderator: Jean-Yves Coffre, Director, Camac, France. Jean-Yves Coffre’s presentation is supported, in part, by a TransCultural Exchange Travel Grant, and made possible by the generosity of Mrs. Ralph Ghormley. Fellow panelist members are: Moez Surani and Nina Leo, Poet and Multi-disciplinary Artists collaboratively working with language and scent; Alia Farid, Curator, Kuwait Pavilion, 14th International Architecture Exhibition, Venice Biennale; Luigi Galimberti, Co-Coordinator, Transnational Dialogues, whose presentation is supported, in part, by a TransCultural Exchange Travel Grant, made possible by the generosity of Mrs. Ralph Ghormley; Flavia D’Avila, Performer and Guest Member, Cultural Policies Committee and Binational Cultural Committee of Santana do Livramento, Brazil.

The panel could also be a moment to meet with me, if you happen to be in Boston, and discuss future projects and activities that we are developing for Leonardo Electronic Almanac (LEA) and the Arts Administration @ Boston University.

Abstract: What does it mean to develop an artistic practice between cultures on the rise and cultures in disappearance? Is it possible to envisage an aesthetic of transformation devoid of conflict?

The paper will address the conflict and the differentiation between ‘this humanity’ and ‘that humanity’

The importance of existing in the locus in order to understand and experience fractures, conflicts and problems, becomes a fixed fixture of contemporary aesthetic global interventions – which increasingly have less to do with the development of a critical artistic practice and more to do with the satisfaction of re-confirming preconceived cultural constructs, stereotypes subjugated to ideological stances and dogmatic perceptions of body politics which are disconnected from critical analyses and experiential practices.

In this context the artist has to negotiate between local and global practices by separating the two and filtering content for each activity taking the risk of either becoming all things to all audiences or confronting both local and global audiences, disregarding their expectations and wants.

The essay will conclude by exploring the possibilities and the lack of possibilities – within a world increasingly characterized by divides and conflicts – to develop artistic practices that are beyond the dichotomy of acceptance and rejection.